Beyond the “One Plan” of IBP

For three decades, Integrated Business Planning (IBP) has promised to bring order to the corporate cacophony. Its pitch is simple and reassuring: convene the right people every month, look twenty‑four months ahead or more, and align strategy, portfolio, demand, supply, and finance into a single operating plan the company stands behind. In the mainstream description, IBP is the formal way a business is managed, a disciplined, exception‑driven, monthly re‑planning process that yields one accepted plan.1

The cadence is familiar: portfolio choices, a demand view, a supply view, and a reconciliation that rolls into a management business review. That cycle, popularized by the originators of S&OP/IBP, typically sits on a 24‑ to 36‑month rolling horizon and helps senior executives look at risks and opportunities with a common language. In short, IBP is a governance framework for conversations about the future.2

Done well, these routines are not without merit. Independent observers report that mature IBP programs can lift operating profit, improve service, and reduce capital intensity when they truly link volumes and financials and when decisions are owned by P&L leaders rather than by a single function. But even in sympathetic assessments, monthly IBP is still a meeting‑centric construct; the frequency is typically monthly, sometimes quarterly, and its outputs are a “unified plan” and an agreed view of risks and scenarios.3

I do not dispute the value of governance. I dispute its sufficiency.

What the business actually needs

Supply chain is not the art of producing a plan. It is the craft of making profitable commitments when the future refuses to sit still. In Introduction to Supply Chain I argue that the practical objective is to raise the firm’s profit—expressed per unit of scarce resources such as capital, capacity, time, and goodwill—after we account for risk. That requires treating every replenishment, allocation, production, transfer, and discount as a wager with real money at stake (Chapter 3, “Epistemology”; Chapter 4, “Economics”).

If we take this stance seriously, three consequences follow.

First, uncertainty cannot be flattened into a single figure. Demand, lead times, reliabilities, and returns arrive as probability distributions; they do not fit into a “one number” box without losing the very tails that ruin naive plans (Chapter 8.4, “Deciding under uncertainty”).

Second, trade‑offs must be priced in money to be comparable. Shortage pain, aging, congestion, late fees, the option value of waiting—each deserves an explicit price tag on a common ledger. Otherwise, meetings devolve into etiquette: percentages are massaged and anecdotes abound, but no one can prove that the next move is the best move in economic terms (Chapter 8.1–8.3).

Third, decisions should be ranked continuously by their expected, risk‑aware return rather than squeezed into a once‑a‑month ritual. Software can do this quietly, at scale, every day. Meetings should set the prices and constraints; engines should make the many small calls that accumulate to performance (Chapter 8.5–8.6).

Where IBP helps—and where it hurts

IBP helps when it forces executives to face the same horizon and speak in the same units. It hurts when that unity is enforced as a “one set of numbers,” and uncertainty is treated as an embarrassment to be averaged away. Even IBP’s own literature leans on the promise of a single operating plan and, explicitly, a “one set of numbers” doctrine—an understandable response to organizational chaos, but an unfortunate one for decision quality when the world is lumpy and adversarial.1

Consider two familiar temptations that shadow “one‑plan” thinking.

The first is consensus theater. Endless pre‑reads and workshops drive convergence to a tidy narrative. Yet a narrative cannot ship a container, nor can it price a stockout correctly. In practice, consensus flattens distributions and erases tails—the very phenomena that determine whether a gamble earns or burns cash when reality deviates from the median (Chapter 8.4; Chapter 8.6).

The second is proxy worship: service‑level percentages and forecast accuracy targets are taken as ends in themselves. Raise the target and buffers swell; shorten horizons and accuracy “improves”; neither move proves that profit was created. Goodhart’s Law has shop‑floor effects (Chapter 3.2.3, “The pitfalls of safety stocks”; Chapter 1, “Primer,” on forecast‑accuracy gaming).

Neither problem is solved by scheduling another review. A monthly drumbeat does not turn percentages into prices, nor does a single plan create agility. Even strong proponents of IBP acknowledge that the cadence is monthly by default and that short‑term execution must be handled elsewhere, often with more frequent iteration. That is a tacit admission that meetings, however well choreographed, cannot substitute for a daily engine of choices.3

A better division of labor

Keep the table, change the agenda.

Use the executive forum to do what humans do best: set prices and constraints that reflect the firm’s appetite for risk and return. Price stockouts, aging, congestion, late fees; state shadow costs of capital and the premium you are willing to pay to keep options open. Make these numbers explicit, auditable, and company‑wide so that arguments are decided by economics rather than by volume in the room (Chapter 8.1–8.3).

Feed those prices to an engine that carries uncertainty as distributions, not slogans. Let it propose the next admissible move—purchase, transfer, production, allocation—because, under the stated prices and constraints, that move has the highest expected gain after risk. Run this quietly and continuously; judge it on the ledger, not on how comforting its outputs look on a dashboard (Chapter 8.4–8.6).

Governance then has a crisp role. If an IBP session exists, it should not be a ceremony of number‑massaging. It should be a forum that changes the economics: adjust penalties and thresholds, add or remove constraints, decide on postponement or late binding where it buys real option value, and revisit the time constants—the half‑life of commitments—so the organization can change course faster next month than it did last (Chapter 8.6; Chapter 4.4).

When described this way, IBP is a wrapper around an economic engine—not the engine itself. Even advocates of IBP, to their credit, emphasize that the process must be owned by P&L leaders, integrated with finance, fed by scenarios, and linked to execution. Where they stop is where the work begins: replacing consensus and proxies with priced uncertainty and automated, auditable decision‑making.1

What to keep from IBP—and what to let go

Keep the cross‑functional ownership, the finance linkage, and the long horizon. Those are conditions for adult conversations, and the IBP canon is right to insist on them, including the 24‑plus‑month lens and the explicit reconciliation of risks and opportunities. But retire the idea that the outcome must be “one number.” The outcome should be a priced stance: which tails matter, how much pain the firm accepts at the margin, what option premiums it will pay, and where deferral and postponement beat early binding.1

If you want proof that governance alone is not enough, look to the fine print of the glowing case studies: even they concede that monthly IBP must be coupled with data, analytics, and near‑real‑time execution to deliver the touted benefits—and that without disciplined inputs, IBP meetings degrade into reviews rather than decisions. The best implementations move closer to an economics‑first posture, sometimes without naming it as such.3

Closing

IBP’s promise was to align the enterprise around a shared view of the future. Alignment is useful, but it is not performance. Performance comes from many small wagers made under uncertainty, priced correctly, executed promptly, and judged by the ledger. That is the stance I defend in Introduction to Supply Chain—see Chapter 4 (“The goal of supply chain”), Chapter 8 (“Decisions,” especially “Deciding under uncertainty” and “Changing course”), and Chapter 3.2.3 (“The pitfalls of safety stocks”).

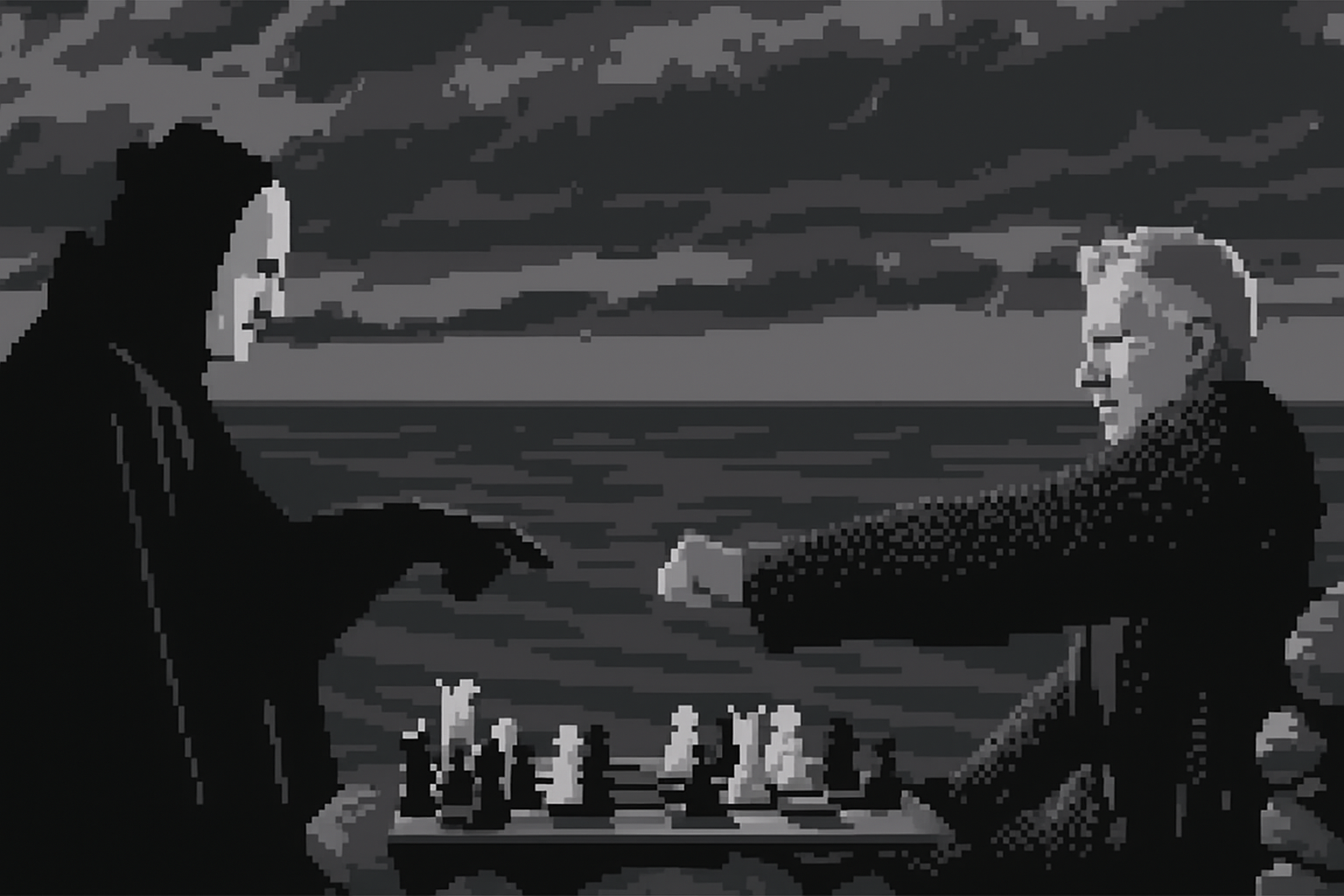

If you must choose, choose economics over ceremony. Better still, keep a simple governance shell and let a probabilistic, price‑aware engine do the heavy lifting. A company doesn’t win by agreeing on a plan; it wins by making better bets, faster, with eyes wide open to the future’s unruly shape.