The SCOR of Supply Chain Belongs to History

There was a time when a single scorecard promised discipline for a world that felt undisciplined. The Supply Chain Operations Reference model—SCOR—codified processes, organized metrics, and taught a generation how to name what they were doing. For that contribution, it deserves respect. Yet the very success of SCOR encouraged a habit of thought: manage the chain by managing attributes, and excellence will emerge from alignment and benchmarking. That habit made sense in an era when computation was scarce and data was brittle. It makes less sense when decisions can be recalculated in milliseconds and tested against tomorrow’s realities before a truck even moves.

APICS—today ASCM—defines supply chain management as the design, planning, execution, control and monitoring of supply‑chain activities to create net value, build infrastructure, leverage logistics, synchronize supply and demand, and measure performance globally. That is a managerial program, not a scientific one, and it is explicit about its scope.1 Elsewhere in the APICS tradition, a supply chain is described as the global network that delivers products and services from raw materials to end customers through an engineered flow of information, physical goods, and cash.2 SCOR then organizes performance into five attributes—reliability, responsiveness, agility, cost and asset management efficiency—and deploys hundreds of metrics to assess progress.3 The modern “SCOR Digital Standard” goes further: it makes the framework open‑access, adds sustainability, and talks about moving from a linear chain to a synchronous network.4 The promise remains consistent: adopt a common process language, measure what matters, and improve in a coordinated way.5

I approach the subject differently. In Introduction to Supply Chain I began with a definition designed to be falsifiable by outcomes, not by conformance: supply chain is the mastery of options under uncertainty in the flow of physical goods (Chapter 1). The point of that phrasing is to foreground decisions and their consequences. If two policies use the same trucks and warehouses but yield different cash flows a year from now, the better supply chain is the one whose choices created the better future. That is not an aesthetic preference; it is the basic arithmetic of the firm (Chapters 1 and 4).

Here the distance from SCOR is not in values but in method. SCOR is multi‑attribute by design. It tells you to balance reliability, responsiveness and agility—customer‑facing ideas—against cost and assets—internal ideas—and to benchmark your mix against peers.6) My method is single‑ledger. Price everything that matters in money, including service promises and risk, and select the policy with the superior expected, risk‑adjusted return over the horizon that truly binds you (Chapters 4 and 12). If you want higher fill rates next quarter, fund them explicitly: hold more stock, buy more options on capacity, or shorten lead times at a price. If you want agility, pay for the setup work that creates alternatives when forecasts go wrong. By putting every lever on the same ledger, the trade‑offs stop being virtues in search of a balance and become investments in search of a return.

SCOR is also ceremony‑forward. It thrives in settings where success means that the planning rhythm was observed and the KPI tree was updated. Its preferred ritual is S&OP: plan demand, plan supply, reconcile, repeat. ASCM remains a vigorous advocate of this cadence, promising removal of “surprises” through a single set of numbers and cross‑functional consensus.7 I prefer to begin with the future as it actually arrives: irregularly, noisily, and often uncooperatively. In the book I contrast a teleological vision—fix tomorrow with a plan—with a rugged one—preserve room to maneuver and act when the option to wait has lost its value (Chapter 7). The ritual is not the point; the decisions are. If a monthly meeting is the fastest way to change course, you are not moving fast enough.

Computers sharpen the disagreement. SCOR focuses on processes, people, practices and metrics; even in its digital standard, computation is presented as an enabler of a model whose center is organizational rather than algorithmic.3 That posture made sense when software mostly recorded transactions and summarized them. But modern software can do better than describe yesterday. It can enumerate the alternatives you are ignoring, simulate their consequences, and execute choices automatically when the evidence is sufficient. In the book I argue for a clean separation between the systems that remember what happened and the systems that decide what should happen next, with the latter engineered to run unattended once they are proven (Chapters 5–6 and 8). The planner’s judgment is not removed; it is concentrated upstream, where we choose policies and constraints, and downstream, where we audit outcomes and revise the playbook. In the middle, the computer does what it does best: it explores millions of versions of “what if” without getting bored or political.

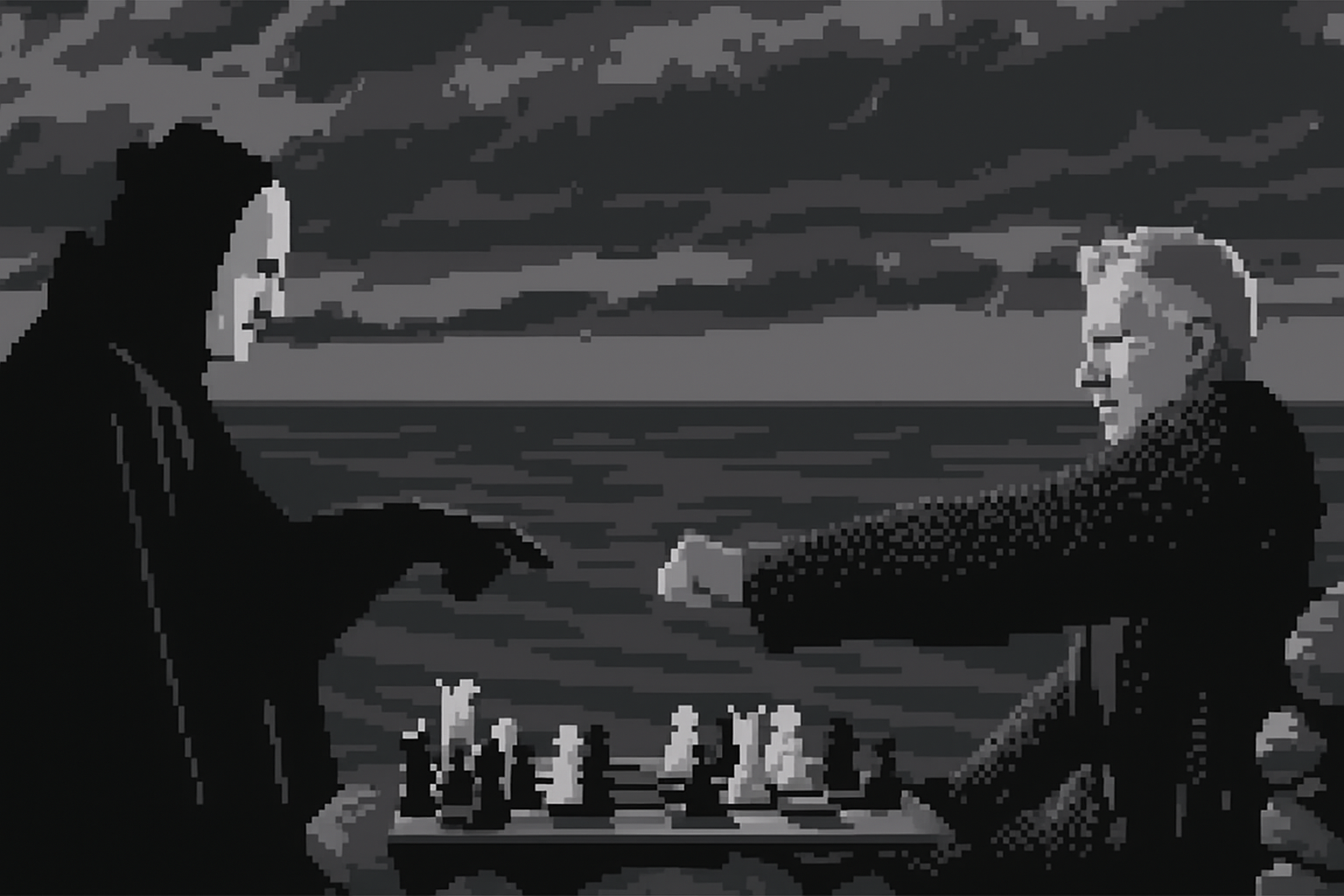

I do not mean to suggest that SCOR is useless. It is useful in the way a grammar is useful: it helps new speakers avoid obvious mistakes and lets organizations talk to one another. But grammars do not write novels, and SCOR does not choose. A firm lives or dies by the choices it makes under uncertainty with scarce resources. That is why the book devotes so much attention to the plain mechanics of economic choice—cash flows, rates of return, timing, and the price of options—because those mechanics ultimately arbitrate between “good practice” and good results (Chapters 4 and 12).

If your organization is fluent in SCOR, keep the vocabulary. Keep the definitions of reliability and responsiveness if they help colleagues meet you where you are. Then put those words on a single ledger and ask what each promise costs and what it buys. Use your planning meetings to test policies against alternatives, not to sanctify a number. Let the computer surface more options than you can see and take for granted that many of those options will be too small or too frequent for any human to manage by hand. When that happens, you are closer to the craft as I understand it: not managing a chain, but shaping a flow of decisions that continuously exchanges today’s certainty for tomorrow’s gain (Chapters 1, 7 and 8).

SCOR taught us to measure. History will thank it for that. But measuring is not deciding, and supply chain, in the end, is a decision‑making discipline.

References to my book are to Introduction to Supply Chain by Joannes Vermorel: Chapter 1 (definition and framing of supply chain), Chapter 4 (the economics and goal of supply chain), Chapters 5–6 (enterprise software and the role of automation), Chapter 7 (visions of the future and the value of waiting), Chapter 8 (decision‑making), and Chapter 12 (rate of return and discounted cash flows). For the SCOR and ASCM material, see the ASCM definition of supply chain management, SCOR performance attributes and metrics, SCOR Digital Standard and guidance, and ASCM’s description of S&OP.1