Men, Machines, and the Real Work of Supply Chain

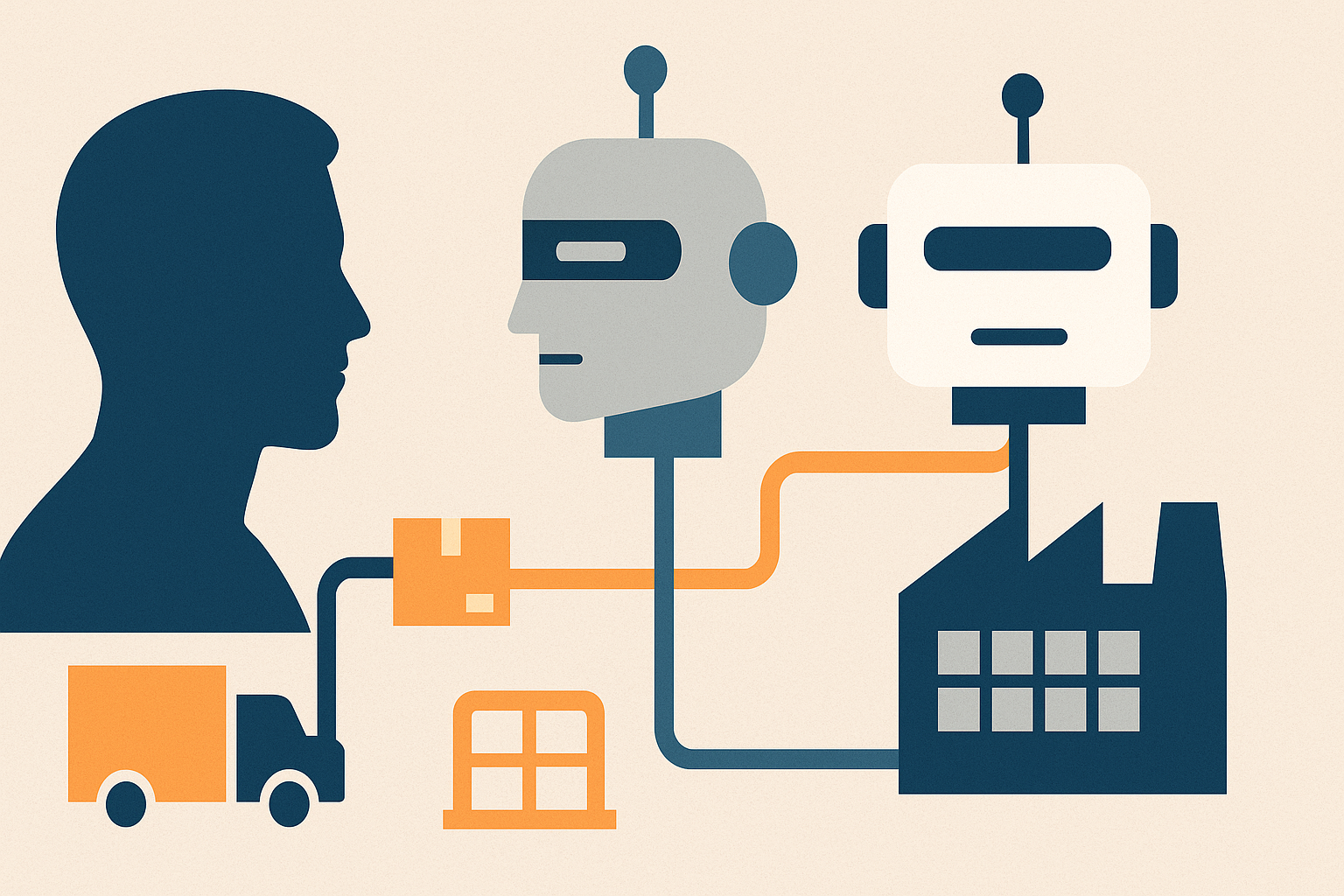

When I sit down with executives to talk about supply chain, they almost always start with warehouses, trucks, people, and sometimes suppliers. Computers appear somewhere in the background: a planning system here, a spreadsheet there, and of course the ERP “that everything runs on.” The implicit picture is always the same: people are at the center, machines are there to help.

I explored a very different picture in my book Introduction to Supply Chain, where I argued that most of what we call “supply chain practice” is, in fact, a software problem in disguise. In this essay I want to restate that idea in plainer terms, and confront it directly with the mainstream view that dominates textbooks and boardrooms alike.

How we quietly demoted computers

In much of the literature and most companies, computers are treated like sophisticated shovels.

You are supposed to have them, of course. No one would manage a global network with paper and fax anymore. Systems capture transactions, store master data, generate reports, and produce forecasts. Planners log in every morning, look at dashboards, combine what the system says with their “business sense,” and decide what to do.

The tone is always similar: technology provides support. It collects data, runs calculations, shows red and green indicators, maybe proposes a recommended order quantity. But the human is expected to “own” the decision. The software is the analyst; the planner is the decision-maker.

On paper this sounds reassuring. It respects experience, intuition, and accountability. It avoids the fear that “the system is running the business.” It fits our intuition that serious decisions should be made by serious people.

The trouble is that this picture no longer matches the scale and complexity of modern supply chains.

Supply chain as a fabric of small bets

Every day, your company makes an astonishing number of small commitments.

You decide how many units of each item to buy from each supplier. You choose which warehouse should receive which quantities. You allocate scarce stock between channels and customers. You accept or reject rush orders. You decide which items deserve shelf space, and at what price. You accept certain lead times from transport providers and reject others.

Each of these commitments is a small bet on an uncertain future: a bet that this order will arrive on time, that this promotion will move the volume, that this safety stock will be enough but not too much. None of these bets is particularly heroic on its own, but taken together they make or break the P&L.

The distinguishing feature of modern supply chains is not that they are global or fast; that is already familiar. It is that the number of such bets has exploded. Product ranges grow. Channels multiply. Lead times fluctuate. Customer expectations rise. The “decision surface” becomes too large for any team of humans to monitor, let alone optimize, by hand.

In this environment, the mainstream model—humans in the center, machines providing decision support—simply does not scale. People become bottlenecks in the wrong place: not at the port or in the warehouse, but in front of screens.

Why computers belong at the center

Computers have one superpower: they are very good at doing a large number of small, structured calculations, over and over, without getting tired or bored.

Supply chain is precisely that kind of problem. Most of the operational decisions that consume the time of planning teams are repetitive. They repeat day after day, with variations in data but with a similar structure. They have clear inputs: forecasts, costs, capacities, constraints, business rules. They have clear outputs: quantities, dates, locations, prices. They are not trivial, but they are structured.

When you accept this, a different architecture suggests itself.

Instead of thinking of computers as tools to prepare information for humans, you start to see them as machines that actually make the routine decisions. Not “assistant” machines, but “decision” machines.

This does not mean building a giant monolithic brain that controls everything. It means deliberately constructing software that, under normal circumstances, can:

- read the relevant data,

- evaluate many possible options,

- choose one according to an explicit economic objective,

- and issue a concrete instruction: a purchase order line, a stock transfer, an allocation, a price.

Humans still exist in this world, but they no longer spend their days nudging individual orders. They work around the decision machinery rather than through it.

That is the core shift: from computers that support decisions to computers that take decisions in all the places where decisions are small, numerous, and repetitive.

What people are actually for

Putting machines at the center does not make people less important; it makes them responsible for different things.

First, people must decide what the software is allowed to do at all. This means defining the space of admissible options. Is cross-docking permitted between these sites? Are substitutions allowed between these two SKUs? Can we ship partial orders to this customer? Can we use air freight for that product in that region? Computers do not invent options; they select among those we make available.

Second, people must decide what “good” means. This is not a matter of vague aspirations like “service excellence” or “lean inventory,” but of explicit tradeoffs. How painful is a stockout, in financial terms, for different products and customers? How expensive is obsolescence? How much do we really value lead time versus cost on a lane-by-lane basis? How should we arbitrate between two business units competing for the same limited capacity?

When we answer these questions precisely, we give the software an objective function. We tell it what we want, in a language it can apply to every decision.

Third, people must guard the meaning of the data. Over time, fields in a system are reused, reinterpreted, and abused. A column once meant “promised delivery date” and now sometimes means “requested date.” A flag that once indicated a product family is quietly repurposed to indicate an internal promotion. If no one pays attention, the software will continue to calculate very precise nonsense.

Finally, people must intervene when the world changes faster than the models or rules. They must be able to say: this constraint is no longer valid; this penalty is too high; this sourcing option is now politically unacceptable; this lead time is no longer trustworthy. They do not intervene by hand-editing thousands of orders, but by changing the assumptions that generate those orders.

So in this view, humans are not clerks polishing spreadsheets. They are designers, economists, and guardians of the decision machinery. Their job is to design the game, set the score, and watch for when the game no longer reflects reality.

The mainstream view, stated plainly

Let me now spell out the mainstream view in a way most practitioners will recognize.

In a typical company, the software landscape has three layers.

At the bottom, transaction systems record what happens: orders, receipts, shipments, invoices. Above them, reporting tools and dashboards summarize that history in many slices: by product, customer, region, time period. On top of that, you find planning systems that take data from below, crunch forecasts, run heuristics or optimizations, and produce “proposals.”

Those proposals are then examined by planners. They check them against their knowledge of the market, the quirks of suppliers, the politics of customers, the reality of warehouses. They accept some, adjust others, and override the rest. In many organizations, large parts of this last step happen in spreadsheets, outside of any formal system.

The implicit philosophy is clear: systems are there to inform and assist. Humans, especially planners, are there to decide. If something goes wrong, the explanation is often that “the system is not flexible enough,” or “the data was wrong,” or “the algorithm did not understand this special case,” so we “needed a planner to correct it.”

Textbooks reinforce this pattern. Information technology is described as a “driver” or an “enabler” of supply chain performance. It provides visibility, integration, speed, and analytical sophistication. But there is always a step where the human decision-maker reappears at the top of the pyramid, to whom the system reports.

This picture is not entirely wrong. It captured the reality of what was feasible for a long time. Systems were rigid. Optimization at scale was expensive. Data quality was terrible. Putting a human in the loop was a safe and pragmatic decision.

But we have stayed with that model longer than it deserves.

Where I part ways with the mainstream

My disagreement with the mainstream can be expressed in one simple sentence:

For most operational decisions, we should no longer aim for decision support; we should aim for decision automation.

This does not mean blind automation. It means that when a decision is small, frequent, and structurally similar across many instances, we should engineer software that takes it end to end, with humans focusing on the design and monitoring of the mechanism rather than on its day-to-day execution.

From this simple statement, several confrontations follow.

The mainstream invests heavily in adding more dashboards and more planners. I would rather invest in fewer planners who behave more like quantitative product owners and more engineers who can encode business logic in code instead of configuration.

The mainstream tries to buy systems that are “configurable” enough to handle most situations out of the box. I expect that any serious supply chain will contain many firm-specific quirks and constraints that cannot be captured meaningfully by checkboxes and parameter tables alone. At some point, someone has to write code.

The mainstream treats the combination of ERP, planning modules, and BI as a completed stack: data at the bottom, insight in the middle, decisions on top. I see that stack as only half-built. The missing layer is the one that takes responsibility for most of the actual commitments in the business.

Above all, the mainstream insists that humans remain the ones “making” the decisions. I insist that, for the vast majority of routine decisions, humans are better deployed deciding how decisions should be made, not making them one by one.

“But what if the system is wrong?”

A common objection is immediate and legitimate: what happens when the system is wrong?

If we let the software place orders, allocate stock, and set prices, and the software makes a mistake, the consequences can be severe. With a human in the loop, at least someone could have caught it.

I believe this objection is important, but it cuts both ways.

When you rely on humans to fix the output of systems that are fundamentally mis-specified, you trade one kind of failure for another. Individual errors might be caught, but structural errors persist. No one has the time or cognitive bandwidth to see that the entire logic of the system is slightly off, that a penalty is miscalibrated, that a constraint has drifted. People firefight; they rarely redesign.

In an automated setup, you are forced to treat this risk explicitly.

You need monitoring that does not just look at service levels and inventory turns, but can attribute failures to specific assumptions. You need the ability to pause automation for a subset of products or regions when an anomaly is detected. You need audit trails: clear records of why the system chose a particular decision, with which inputs and which internal logic.

Most importantly, you need a culture that accepts that software is a first-class asset. It deserves design, testing, refactoring, and governance. It cannot be an opaque black box that “the vendor handles” or “IT takes care of.” If the software is running the day-to-day business, then enriching and correcting its behavior is one of the core responsibilities of the supply chain organization.

That may sound riskier than asking planners to “keep an eye on the proposals,” but in practice it often reduces risk rather than increasing it. Failures are more traceable. Fixes are systemic rather than local. Learning accumulates in code instead of disappearing when an experienced planner leaves.

Where I still agree with the mainstream

Despite these disagreements, there are areas where I am fully aligned with the mainstream view.

I agree that information is central. Without timely, reliable data, any ambition for automation is fantasy.

I agree that organizational silos are a major obstacle. If procurement, logistics, sales, and finance cannot agree on basic definitions and shared objectives, no system will rescue them.

I agree that supply chain is not only about math and machines. Relationships with suppliers, trust among partners, regulatory constraints, and geopolitical shocks all matter enormously. A beautiful decision engine cannot make a ship appear in a blocked canal.

My point is more precise: when it comes to the daily work of deciding quantities, timings, and allocations across large networks, we are dramatically underusing the machines we already have. We are trapping talented people in clerical loops where they add very little marginal value, but absorb a huge amount of organizational energy.

A different destination

If you take my view seriously, the destination looks something like this.

Most day-to-day operational decisions—what to order, where to allocate, how much to ship, when to replenish—are taken automatically by software, under normal circumstances. The software operates under clear, explicit rules and economic objectives, and its behavior is visible and auditable.

Planners do not start their day by scrolling through exception lists. They start their day by looking at the behavior of the decision machinery itself: where it is performing well, where it is erratic, where assumptions may have become stale. They work with engineers to refine the logic, improve the data, adjust the economic tradeoffs.

When disruptions occur, humans step in not by micromanaging individual orders, but by changing the parameters of the game: forbidding certain transport modes, opening temporary sourcing options, revising penalties and priorities. The system then recomputes the myriad small bets implied by those new conditions.

Careers in supply chain evolve accordingly. Less time is spent on “fighting the system” and “fixing the plan.” More time is spent on understanding the economics of the business, encoding that understanding in software, and designing resilient option sets for an uncertain world.

In such an organization, the computers are no longer shovels. They are the machinery of the supply chain. People are the architects, economists, and stewards of that machinery.

That is the perspective I wanted to clarify here. It differs sharply from the mainstream narrative of IT as support and people as primary decision-makers. But I believe it is closer to the reality of where supply chains can, and should, go next.