Micro fulfilment

Micro fulfilment is a strategy used by retailers to improve the efficiency of the e-commerce order fulfilment process. This entails receiving the order, packing and then last mile delivery. A micro fulfilment center (MFC) typically stocks fast-moving SKUs, as opposed to every product on offer, in multiple limited-capacity facilities situated close to the end customer (usually located within city limits). Routinely, they will use a software management system, a physical infrastructure, and packing and delivery staff.

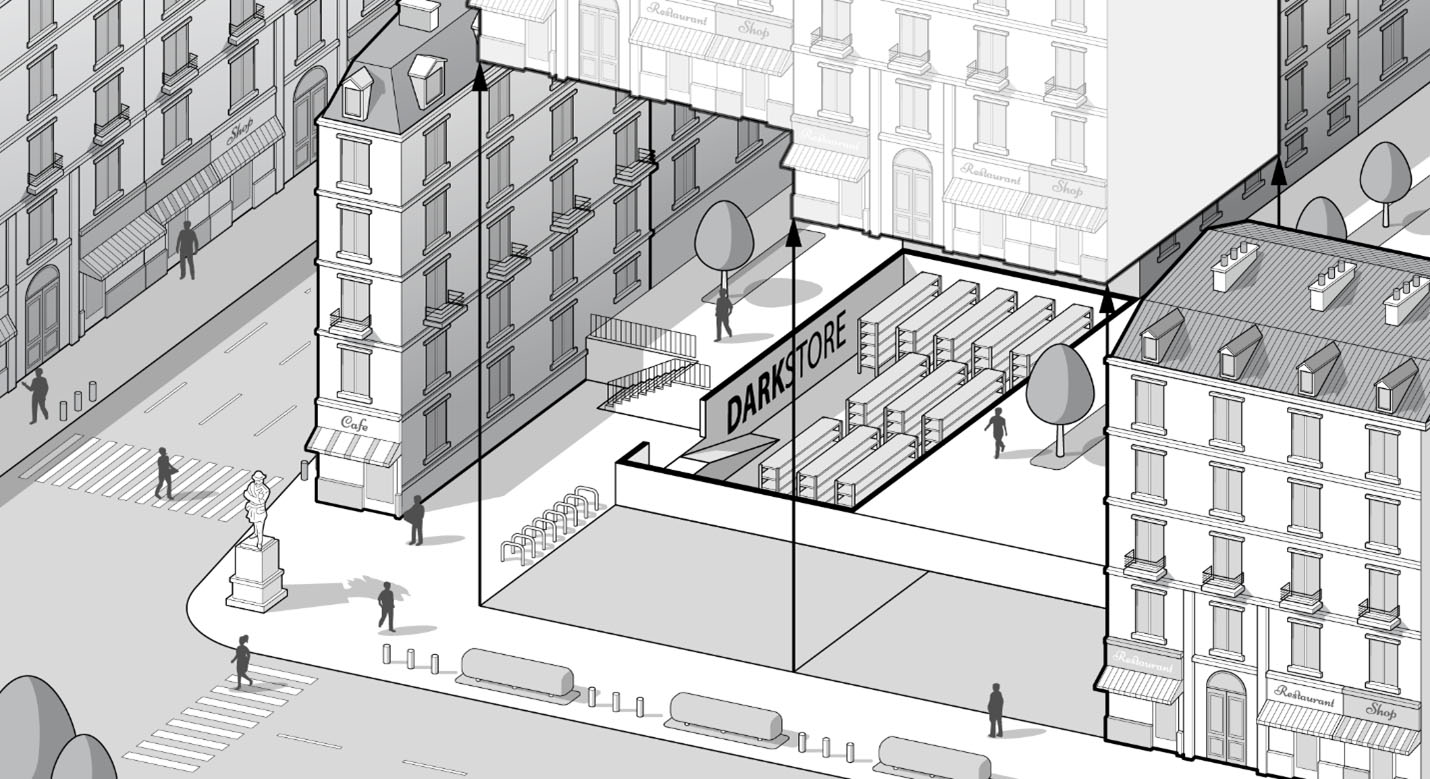

Figure 1: A dark store situated in a city center using secondary real estate. In this example, the dark store is below ground level in an existing infrastructure but, crucially, still has access to street level. Shelving is densely packed in the small underground space with minimal spacing between gondolas, and the facility is optimized for picking and packing operations. Bicycle racks can be seen nearby so that MFC employees can conveniently leave their bicycles while picking up deliveries.

Background

Micro fulfilment emerged at scale in the mid-2010s with retail specialists operating through dark stores to establish a unique selling proposition through same-day deliveries. Since then, micro fulfilment third parties have also emerged, selling their services to traditional retailers, and contributing to a gradual commoditization of micro fulfilment. In both cases, intimate knowledge of the ultra-local1 area to deliver to the final customer is essential.

MFC forms and characteristics

Micro fulfilment centers take two main forms. The first form consists of a dedicated area in an existing infrastructure, such as a retail store. This type of MFC is usually installed in areas that are less useful and valuable than the rest of the store, such as at the back, underground, or a small upstairs area. The MFC is kept isolated from the rest of the store’s activities, thus producing two chief benefits (beyond the reduced delivery time itself): first, shelves are optimized for employees to find and select the required inventory; second, as employees know specifically where the fast-moving SKUs are stored, the dedicated MFC area reduces disruptions.

The second form, sometimes referred to as a dark store (see Figure 1), is a standalone facility, possibly owned by an external entity that then rents out the space to multiple different retailers. A dark store only hosts last mile delivery functionality, with all activity optimized to increase efficiency and reduce consumer waiting time (CWT). Dark stores, also known as dark shops, dark supermarkets or dotcom centers, are the embodiment of real estate opportunism. A dark store is a brick-and-mortar location that has been turned, sometimes temporarily, into a fulfilment center for online shopping. A dark store can also take the form of a small regular store that has been shut down and converted to accommodate fulfilment operations. These small, tightly packed spaces have no cashiers and do not organize their shelves for merchandizing purposes. Their only purpose is to fulfil orders and convey them to the final customer as efficiently as possible. Shelves are organized to optimize picking and packing, holding a reduced range of fast-moving goods. Dark stores get their name from the idea of being hidden and closed off from the shopper. The customer is uninformed or “in the dark” about the facility. The name is also reminiscent of a dark factory,2 which refers to a fully-automated factory where no worker operates.

These dark stores are routinely in unconventional spaces, further helping to reduce rental costs. For example, in London some micro fulfilment players are setting up in the arches underneath railway lines, which often have no other usage. These locations are unattractive, in obsolete infrastructure, or on back streets, away from the high street or main shopping areas. While this would be detrimental for regular stores, MFCs are not affected by these inconveniences because they are not intended for direct customer traffic.

It should be noted that both MFC forms described here make use of secondary real estate, rather than prime real estate. By secondary real estate we here refer to square meters which are, for whatever reason, below the usual market value for that area. Conversely, prime real estate refers to square meters that make the most of what the urban environment has to offer, for example, shelves facing customers in an area with high traffic. Secondary real estate is typically much cheaper than prime real estate.

Understanding MFCs

There is significant overlap between the two MFC forms described above. Both arrangements require access to street level, are usually small in size and therefore have limited SKUs, and the layout of the space is organized for pick and pack operations. Both forms feature shelves that are optimized for operating efficiency and each product is close at hand, meaning the employees do not have far to walk to find the required inventory. Additionally, both types of MFC are conceived with flexibility in mind; areas of a preexisting store can always be reconfigured as demands dictate, and a dark store can be quickly abandoned or relocated if needed. This differs extensively from a merchandising setup used in customer-facing retail situations. In these scenarios, the layout is designed to get the shoppers to circulate about the store so that they are exposed to more products, in the hopes they may buy a little more than they initially planned.

These micro fulfilment centers are much closer to the end customer than the mainstream method of order fulfilment in e-commerce, known as macro fulfilment. While MFC facilities leverage depreciated real estate within the urban area, macro fulfilment, conversely, uses a centralized fulfilment center (CFC), which is large and on the city outskirts, much further from the end customer. Unlike MFCs, the CFCs are customarily intended to be permanent sites, benefiting from substantial investments and a high degree of automation.

A growing trend of the 2020s

The e-commerce industry has been growing since the mid-1990s and is on track to overtake local commerce. In parallel, micro fulfilment is emerging as a competitive alternative for all local retail segments, including pharmacies, general stores and department stores. Among those, local groceries represent the biggest market to partially transition towards micro fulfilment. Importantly, it is likely that this vertical is where micro fulfilment’s added value for the customer is most noticeable, given its potential for rapid delivery.

Customer expectations also changed during the 2000s, largely due to e-commerce leaders like Amazon who established a new gold standard of customer experience both in terms of delivery times and reliability. Nowadays, customers expect highly reliable deliveries, with receipt of goods forecasted with precision measured on the hour-level.

Since the mid-2010s, more and more players in the grocery space have begun to leverage MFCs, with actors in adjacent businesses (such as delivery of restaurant meals) pivoting to also provide grocery delivery. This trend is not limited to heavily funded startups looking to capitalize on increased customer expectations. Rather, many preexisting sector leaders are pivoting to an MFC position, such as Tesco in the United Kingdom. These players use multiple dark stores in densely packed urban environments to facilitate the fastest possible delivery.

These moves coincide with the recent surge in online grocery purchasing: 36.8% of US consumers bought groceries online in 2019, up from 23.1% in 2018.3 E-commerce saw considerable growth during the Covid-19 pandemic, where customers were much more likely to buy online due to lockdowns. To service this demand and remain competitive, Walmart is using over 5,000 of their stores in the United States as MFCs.4

Though consumer demand is clear, and there are players eager to satisfy this demand, the future of dark stores is subject to tricky legal constraints. For example, as of 2020 it is estimated that Paris is home to around 150 dark stores, compared to 7,682 regular food shops5 Under French law, however, these dark stores are considered food warehouses and, as per local restrictions, installing and operating a warehouse in a residential building (e.g., in the city center) is illegal. These buildings are also subject to police inspection and, as of March 2022, of the 65 police inspections of known dark stores, 45 were found to be illegal.6 Furthermore, Paris city hall receives dozens of complaints each week, mostly due to the regular noise from scooters picking up deliveries late into the night and during early morning hours.

Real-estate opportunism

As an economic model, micro fulfilment is most suited to dense urban environments7 where real estate is scarce and expensive. As a consequence, micro fulfilment encourages an approach of real estate opportunism. In order to stay competitive, actors have to constantly watch their local urban areas to find suitable locations to use as dark stores, and they are especially opportunistic in their choice of location in inner-city areas. Fully leveraging secondary real estate requires opportunistic management and a nimble “on the move” mentality. Optimal locations may present themselves unexpectedly or, as previously mentioned, become inoperable due to external forces. As such, operators need to be able to act quickly. Per contra, large retailers are typically geared towards operating in permanent locations, and thus do not necessarily operate within a culture that promotes the opportunistic leveraging of real estate for potentially transient data store locations. Their culture gravitates more towards permanent centralized warehouses, normally on the city outskirts. Thus, when these larger retailers perform micro fulfilment, the easiest option is to leverage their permanent, preexisting locations, though this may not be as competitive.

Given all these considerations, it is likely that the most successful micro fulfilment actors will be the ones who are able to take advantage of the urban environment’s ‘chaotic’ nature, and capitalize on its secondary real estate in order to operate more profitably. Though secondary real estate is often sparse and of low quality, it is, crucially, relatively inexpensive compared to prime retail real estate. As previously discussed, it can also be leveraged on a short-term basis, for example, a building may be empty for several months between the old tenant leaving and the new tenant arriving. The capacity for a micro fulfilment actor to quickly move into a location and set up the equipment, and quickly leave if/when the time comes, is a competitive advantage compared to less agile actors.8

Value proposition: the retailer perspective

The primary driver for a retailer to adopt micro fulfilment is to capture market shares by offering a superior online shopping experience to its customers. However, compared to CFCs, MFCs can offer a more cost-efficient way to execute the service as well. The following is an inexhaustive array of the primary benefits:

MFCs being located in cities and urban centers naturally brings the products closer to the customer, and so transportation costs are reduced compared to shipments from outside the city, as is the case with CFCs. The overheads generated by last-minute changes of plans are also much lower, again due to the proximity between the MFC and the customers.

MFCs are quicker, easier and cheaper per square meter to set up than regular warehouses and CFCs, in part due to their basic style (though a chief downside of this approach is a lack of automation for picking and packing). A regular warehouse is normally around 30,000 square meters, whereas MFCs usually range from 100 to 300 square meters,4 though in densely packed urban environments, 5 to 10 square meters is not uncommon. As a result, they can be set up in a short time period, typically between two days and two weeks. Longer setups are unlikely to be financially competitive, and naturally incompatible with locations that are only available for a limited period of time.

Micro fulfilment may improve the profitability of local commerce. According to the Food Industry Association (FMI), the net profit after tax in the United States groceries industry in 2020 was 3%,9 but this can increase to between 12% - 16% after the introduction of micro fulfilment.10 This arguably suggests the possibility for explosive growth in this domain. Furthermore, micro fulfilment can help to reduce expenses. According to Jefferies, the MFC approach is superior to all other fulfilment models, eliminating more than 75% of costs compared to manual store-based picking.10 However, these margins are wholly dependent on the amount of inexpensive secondary real estate that is available. Once this resource has been exhausted and more expensive prime real estate is used for micro fulfilment, margins will almost certainly be reduced.

Sustainability and carbon emissions

In terms of freight costs and emissions, the micro fulfilment model is comparable with the local neighbourhood grocery stores that generate typical foot traffic. Both traditional and dark stores leverage inbound truck shipments, at which point a human takes over; a customer enters a grocery store in the former (via bus, bicycle, walking, etc.); or a courier transports the goods (typically via bicycle) in the latter. If the distance is too great or goods too heavy for delivery from a dark store, then the customer must collect the goods in person, most likely with a vehicle, which they would have had to do in a situation without MFCs anyway.

In actuality, some studies suggest that MFCs beget a reduction in overall freight costs and emissions. For example, in 2018 an Amazon-led last mile logistics project was approved in the center of London, designed to repurpose 39 spaces in a public car park. This hub is expected to service a two-kilometer radius without the need for motorized delivery vehicles, supposedly resulting in a reduction of 23,000 vehicle journeys in central London every year.11 Furthermore, Accenture and Frontier Economics modelled the results of fulfilling 50% of e-commerce orders through micro fulfilment in three densely populated cities: Chicago, London and Sydney. The study claims that local fulfilment centers such as these are expected to lower emissions by between 17% - 26% by 2025.12

Alternative approaches to micro fulfilment

Micro fulfilment primarily focuses on optimizing Last Mile Delivery13 but there are several approaches to e-commerce that can partially eliminate last mile delivery costs, namely automated pick-up points and electronic lockers. However one approaches it, strategic intervention is needed in this area as last mile delivery is relatively inefficient and research from 2019 estimated that it accounts for 41% of overall supply chain costs (excluding warehousing, sorting and parceling).14 15

Amazon pioneered the use of electronic pick-up lockers in 2011 and the service is still developing, in part due to the online-shopping boom induced by the Covid-19 lockdowns. In the UK, the Amazon locker network increased from 2,500 to 5,000 between 2020 and 2022.16 Customer goods are delivered to secure, fully automatic self-service kiosks in areas throughout urban environments that would normally be considered secondary real estate. They are often located along unused walls in petrol station forecourts or shopping malls, etc. These electronic lockers are only used for nonperishable goods.

Walmart, in 2017, introduced automated pick-up towers in their stores. This method enables customers to purchase their products online and collect them from in-store vending machines,17 rather than relying on home delivery. This concept, referred to as click and collect or buy online, pick up in-store (BOPUS), is regularly offered inside existing retail stores to help increase foot traffic and sales. Ultimately for Walmart, these in-store vending machines proved unsuccessful and were discontinued in 2021. Seemingly, customers now expect curbside pick-up, thus eliminating the hassle of going inside the store. In a post-lockdown world, this is now commonplace even among small independent stores.

Other variations of click and collect exist, for example remote pick-up where various affiliated stores or post offices are designated pickup points (such as points relais in Paris). Another example is ship-to-store, where a customer orders online and the product is then delivered from a centralized fulfilment center and made available for collection at the store. This is often a possibility when the item that the customer wants is not immediately available at the store and home delivery is not an option.

Though these approaches all boast some degree of effectiveness in eliminating the need for last mile delivery, they do not address the underlying goal of many customers: having their purchases delivered to their home without any additional hassle. Furthermore, there are additional constraints worth considering with the above solutions, such as the availability of refrigerated lockers (without which storing groceries is not a viable option).

Software-driven productivity gains

Micro fulfilment is vulnerable to commoditization due to the relatively straightforward setup of dark stores, and the general lack of entry barriers (potential legal roadblocks notwithstanding). As access to automation is limited in most MFCs (recall the example of the car park project), the dominant cost driver for MFC actors will likely be its workforce. As a result, productivity is expected to be a key differentiator among these players. Thus, the most successful operators will likely be the ones that maximize the productivity of their workforce, typically leveraging software technologies to achieve this efficiency. Such software technologies, which are likely to be extensively integrated into the rest of the supply chain landscape, may represent a competitive edge and entry barrier favoring larger actors.

It is worth noting that the superior productivity described above is also critical when it comes to generating sufficient profit to afford competitive salaries in order to retain productive staff. This is especially vital for MFCs given they operate within a larger gig economy ecosystem with enormous turnover.

There are several predictable problems that can occur within such an environment that may be alleviated with software intervention. For example, time wasted searching for products in the dark store, mistakes made during picking, confusion due to several concurrent orders, inefficient routes taken or time lost searching for a destination, last minute changes from customers, customers not being present at the correct place or time, customers being confused, etc., all carry monetary downstream implications. However, productivity gains can be achieved using software to address these (and other) problems. Software may improve prioritization and picking order through provided checklists, warnings for possible mistakes or easily confused products, route prioritization, reconfigured routes based on last minute information from the customer, etc. That said, such software require a high degree of integration in the broader applicative landscape if they are to be effective.

MFCs, smartphones and the gig economy

An MFC operator’s edge will most likely be defined by their private, in-house micro fulfilment execution systems. The most successful micro fulfilment actors will use sophisticated software to manage the manual operations of employees and optimize their productivity. This software infrastructure is likely to be geared towards smartphones, and possibly the BYOD (‘Bring Your Own Device’) perspective, which is frequently perceived as attractive by the employees themselves. The courier downloads an app that remotely provides all the instructions and relevant delivery information, from which items to take from a conveyor belt to where the delivery needs to go.

A point worth considering is where MFCs, BYOD and the gig economy intersect. IT administration, and overall optimization, becomes more difficult when devices are not company approved/exclusive. Although the BYOD approach is rather convenient for employees, it is less advantageous for MFC operators if their staff work for multiple MFCs, which is common in the gig economy. Given each MFC may utilize their own software, this obliges the freelancer to either download an individual app for each gig (thus potentially compromising device integrity), or carry multiple devices (which may prove unpopular for workers and introduces additional logistical considerations for employers).

Another technological feature that is likely to differentiate players in the space is software driven control towers. Given city streets are noisy and chaotic, the courier on the ground is not necessarily in a good position to answer phone calls or even process “raw” updates from the customer. In such an environment, receiving digestible last-minute information from the customer is a challenge, however a control tower – a mix of operators and automation – delivering high quality updates to the delivery staff can address this issue and reduce friction caused by last minute updates. Unlike MFCs, which by definition must be situated within city limits, a control tower can be located in a cheap area far from the city (or potentially another country), further reducing costs.

Technological misconceptions

A common misconception is that MFCs are highly automated and use wheeled robots (or other futuristic gadgetry) to find and move the products. While some automation may be common in larger MFCs, the majority of MFCs are basic and use no automation whatsoever. They only include foldable shelves, cheap conveyor belt kits, and computer systems. This equipment is usually on wheels, deliberately designed to be transported, moved, and set up with ease. There is often a space for bicycle storage, and potentially somewhere to charge electric bikes, which is fast becoming the preferred mode of transport for this industry. Investing in expensive automation would mean that the micro fulfilment actor would be committed to the location, which runs contrary to the agility that is usually desired.

In 2013, drone delivery was touted as one of the next breakthroughs for fast delivery, potentially within 30 minutes of making a purchase online.18 There are still proponents of this concept who maintain that it is faster, safer and “greener” than regular fulfilment.19 However, the volume of drone delivery remains negligible. While drones are indeed capable of carrying certain items, and over time the carrying range will increase, this idea is not feasible in urban environments. Cities have many obstacles such as trees or power lines, and a lack of viable delivery areas. Infrastructure such as drone landing pads would be required which are not currently readily available, and the cost of this infrastructure, as well as the cost of the drones themselves, may mean that drone delivery is not economically viable. Further problems exist, such as the potential threat a malfunctioning drone, weighed down with packages, poses to pedestrians. City noise rules and regulations may also impede drone use in certain areas. Finally, laws around restricted airspace would prevent deliveries close to airports. These constraints mean that only a select few customers in certain city areas could conceivably benefit from this technology.

There are multiple start-ups offering ground-based autonomous delivery robots that can bypass many of the constraints hindering aerial drone delivery. While some cities have placed restrictions on the use of small autonomous vehicles on sidewalks, these robots remain a possible solution for MFCs. The robots’ relatively small range of around 6 km is ample for a typical European urban environment. However, this is likely an expensive novelty given any robot-traversable route is more easily (and cheaply) traversed by a courier on a bicycle. The latter would also be significantly nimbler in a densely packed city.

Challenges

Providing micro fulfilment is straightforward; being profitable as a micro fulfilment specialist is difficult.

First, the supply chain spread is large. Within a city, having an MFC every kilometer is necessary if one wishes to achieve bicycle courier deliveries in 5 minutes or less. This introduces complexities and frictions that are similar to the ones that apply to large brick-and-mortar retail chains. This conflicts with the relative simplicity that characterizes mainstream, highly centralized e-commerce.

Second, keeping in touch with the customer – via an app or some other channels - requires tight, low-latency integration with all the partners involved in executing the micro fulfilment operation. For example, confusion about the orders, routes taken, door codes, etc., all result in downtimes that translate directly into a loss of productivity. IT glitches, however mundane, can immediately convert into costly overhead. IT-wise, micro fulfilment is more dependent on high quality service and network integrity than macro fulfilment. The often transient nature of dark stores adds its own set of complications, as the edges of the MFC network can be fuzzy (e.g., becoming larger or smaller with very little notice), thus further demonstrating the fine margins between efficiency and waste.

Third, micro fulfilment lacks some of the obvious ‘local commerce’ mechanisms to deal with overstocks and/or perishable stock. Many of the traditional sales methods for offloading expiring stock are unavailable to MFCs. For example, a minimarket can promote perishing stock with a ‘50% off’ sticker and place them in highly visible parts of the store, thus leveraging foot traffic. Some digital equivalents are possible for micro fulfilment – for example, a spot promotion in the webstore – but this requires a two-way integration between the inventory management system and the webstore front-end. This is also an additional productivity step in a process that is engineered to be as administratively lean as possible.

Last but not least, all inventory woes (and associated administrative headaches) are potentially exacerbated: stock-outs and overstocks are harder to avoid and are more costly to resolve when they happen; and, crucially, there is no store manager with plenty of spare time around to smooth out any unexpected stock quandaries. Dark stores also tend to have very low storage capacity (recall 5-10 square meters is not an uncommon capacity) requiring daily planning, which can make stock decisions a dynamic and fluid process (and one ripe for extensive software automation).

Managing this concept requires ongoing predictive optimization to ensure the process is profitable. All of this complexity and diversity is contingent on a wide variety of local situations, and on the specific digital bridge between the retailer and the micro fulfilment player.

For brick-and-mortar retail networks that already operate a vast supply chain network, the main challenge is the IT. Their existing systems may not have been designed with low-latency, third-party system integration in mind. In other words, the requisite high quality of service – “always on” systems – might be incompatible with systems designed around batch processes. Furthermore, the high quality of instrumentation of all the third parties that contribute to delivery is essential to be able to pinpoint the root cause of problems in a chaotic and changing urban environment.

Lokad’s take

The success of a micro fulfilment operation depends on the quality of the product assortment, the quality of service, and the competitiveness of prices. Crucially, these elements all compete with each other. A larger assortment is typically perceived as more appealing by customers, but it exacerbates stock-outs and overstocks. Similarly, competitive pricing means that margins leave little or no leeway to be more accommodating for the customer.

Compared to local stores, the economic performance of the micro fulfilment service is even more acutely dependent on the capacity to deliver “just the right products” with “just the right quantities” at “just the right prices”. Yet, unlike local commerce, extensive software automation to pilot all those decisions is a must-have as any manpower thrown at the situation is pure overhead. Simply put, in a dark store there is no “spare time” waiting for a client to show up; intelligent decisions must be made in advance.

Naïve stocking strategies, such as focusing on top sellers, do not yield high quality of service, as customers do not perceive quality at the SKU level, but at the basket level. Thus, we can invert the paradigm: quality of service is about picking customers who can be served well and profitably, rather than picking products that are easy to stock.

Lokad has developed a technology to put micro fulfilment replenishments on auto-pilot while factoring the major local and nonlocal drivers that shape the demand. It is our contention that probabilistic demand forecasting is essential to coping with the low sales volume that is often observed at the micro fulfilment center level. Differential programming is also necessary to successfully compute and accommodate the vast array of diverse factors and constraints present in a real-world setup.

Beyond replenishment, Lokad can perform stock-rebalancing across micro fulfilment centers and their distribution hubs (when the option exists and is economically viable). Given pricing generally shapes demand, Lokad also offers joint ‘stocking+pricing’ optimization.

Notes

-

Oberlo, 19 Powerful Ecommerce Statistics That Will Guide Your Strategy in 2021

-

Coresight Research, Infographic: Online Grocery Shopping—US Consumer Survey, 2022

-

Micro fulfilment does not have the same meaning in North America where cities usually sprawl over large areas (compared to traditionally dense European city centers). As such, the definition of local can change depending on the location. What is considered local in the United States is unlikely to be considered local in Europe or Asia where cities regularly cover a much smaller geographical area but also have a higher population density. ↩︎

-

A dark factory, sometimes referred to as lights-out manufacturing, is a fully automated facility that does not require human presence on-site. As such, they are (in theory) capable of operating with the lights off, resulting in lower operating costs. ↩︎

-

Coresight Research, US Online Grocery Survey 2019 ↩︎

-

CB Insights, The Next Shipping & Delivery Battleground: Why Amazon, Walmart, & Smaller Retailers Are Betting On Micro-Fulfillment ↩︎ ↩︎

-

L’évolution du nombre de commerces à Paris, La Fondation d’entreprise MMA des Entrepreneurs du Futur, 2020 ↩︎

-

Franceinfo, Paris : les “dark stores”, ces “magasins fantômes” qui excèdent les riverains ↩︎

-

This only applies to Europe because American cities are not as “chaotic”. US cities are generally designed in a grid system by city planners, whereas European cities developed more organically, resulting in greater congestion (particularly in the city centers). European cities are full by definition; there is very little unoccupied land. ↩︎

-

Locations can be transient for a number of reasons, for example, perhaps a building is scheduled for renovation in nine months, or construction work will render a street a dead zone for the next two years. These locations could be viable solutions for micro fulfilment centers. ↩︎

-

The Food Industry Association (FMI), Supermarket Facts ↩︎

-

Fabric, “All Roads Lead to Online Grocery” 2019 Online Grocery Report ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Logistics manager, Amazon Logistics chosen to run City of London’s first lasthub, 2020 ↩︎

-

Accenture, The Sustainable Last Mile, 2020 ↩︎

-

With regards supply chain management, last mile delivery refers to the final part of a product’s journey, consisting of the movement of goods from a transportation hub to a destination, normally the end customer. ↩︎

-

According to Capgemini, supply chain costs in this context do not include warehousing, sorting, parceling, or “other” remaining supply chain costs. ↩︎

-

Capgemini, The last mile delivery challenge ↩︎

-

Financial Times, Amazon doubles UK parcel lockers to take strain off delivery staff, 2022 ↩︎

-

These 5-meter-tall machines were capable of holding up to 300 small- to medium-sized packages and would allow a customer to collect their order within seconds of scanning their received barcode. ↩︎

-

CBS News, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos looks to the future, 2013 ↩︎

-

Manna, accessed June 2022 ↩︎