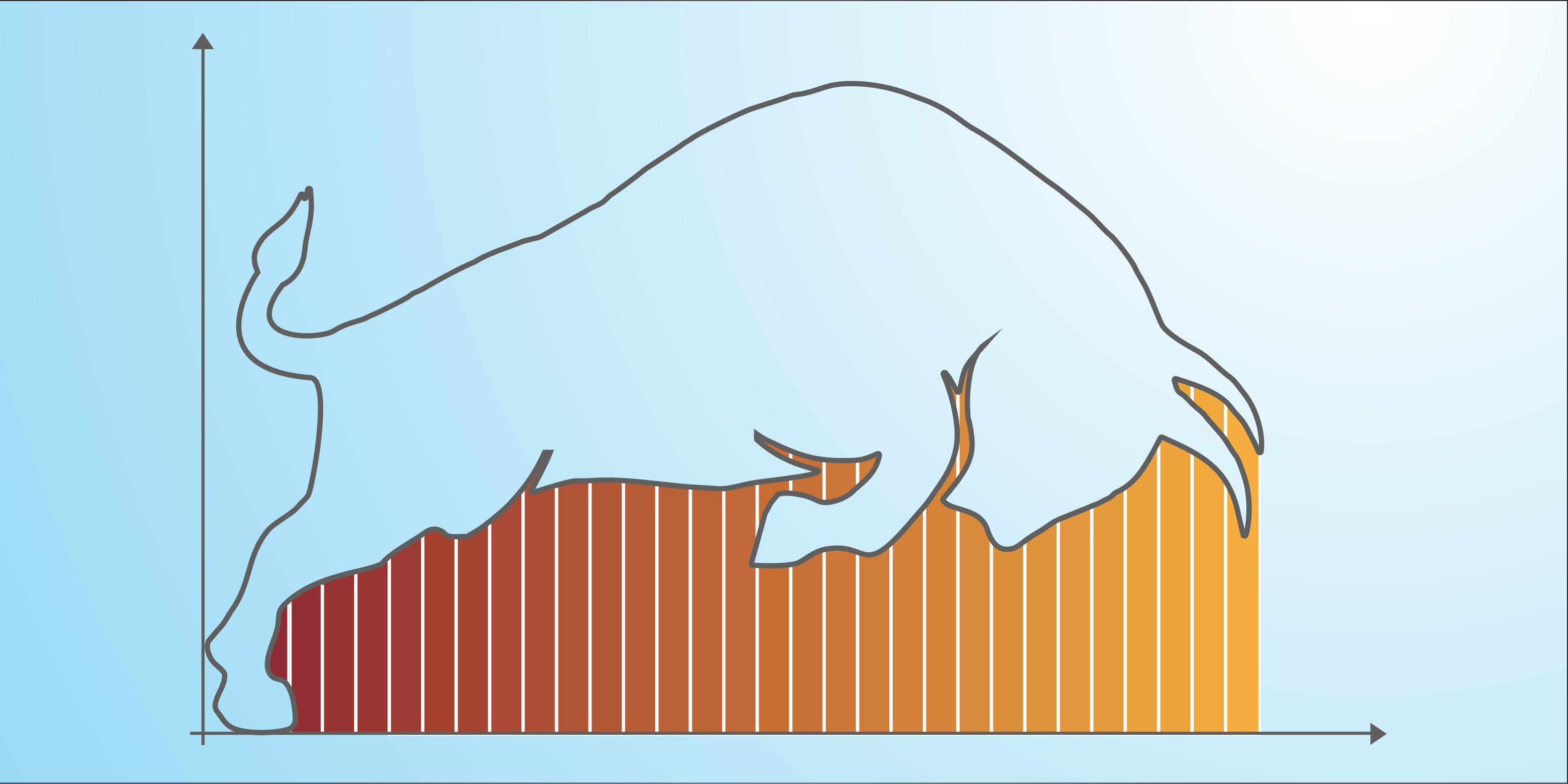

The Bullwhip effect (supply chain)

Within supply chains, the bullwhip effect arises from the amplification of fluctuations going up the chain. While downstream firms may face stable consumer demand, upstream echelons, including suppliers, may experience greater variations due to causes such as price fluctuations, batching, predictive modelling and coordination problems. The bullwhip effect, which was first identified in the 1960s, has become prevalent in a globalized world where supply chains are complex, large, and international. It generates excessive inventories, delays, and poor customer service, especially for industries with many intermediaries. Companies have adapted to meet this irregular demand by smoothing their production and ensuring sufficient stock levels.

Amplification effects in the supply chain

The supply chain can be seen as a system in which companies adjust purchases, production, and prices. The overall goal is to keep supply aligned with demand, faced with random fluctuations requiring constant adjustments to market conditions. Performing these adjustments typically falls under the broad umbrella of supply chain management (SCM).

In this system, SCM decisions can exacerbate fluctuations going up the chain. Considering a simple FMGC example with a store, a regional warehouse, and a factory supplying the entire country, amplifications can arise from batched orders: while consumers buy products only one at a time, the store, for cost reasons, orders pallets from its supplier. Therefore, the regional warehouse is faced with a demand for pallets but can only order full trucks from the factory. In the end, the factory receives erratic truck orders, even though the consumer demand is steady.

In addition, accidental synchronizations, such as calendar orders, cause resonance effects that accentuate bullwhips. If two warehouses get into the habit of placing their orders on Mondays, because it simplifies their internal planning, the result is an order for two trucks instead of one for the factory that day. In this situation, the lack of data can lead the upstream echelon to misinterpret this situation as a demand surge and to increase its production.

Surveying the root causes

Bullwhip effects generally emerge from the intent to achieve economies of scale (batching, promotions) or as a consequence of SCM decision models themselves (predictive modelling, coordination problems).

Promotions

Producers are trying to increase their market shares through promotions and discounts in the marketplace. Faced with price variations, companies buy in quantities that do not reflect their immediate needs and create bullwhip effects. They prefer to buy in bigger quantities and stock up for the future to achieve economies of scale.

Although promotions may seem irrational because they create additional costs for producers, they are a way to nudge markets and alter equilibria. Indeed, temporary discounts concentrate the demand and force producers to stock at great expense, but they also represent an opportunity to gain market shares by disrupting the status quo.

Batching

Batching is companies trying to take advantage of economies of scale through price breaks, batch shipments or production batches. For inventory replenishment, a warehouse does not immediately place an order with its factory. It prefers to batch, or accumulate, requests to reduce the associated costs and achieve economies of scale on delivery.

Batches lead to trade-offs between economies of scale and the problems they create: while large batches reduce production costs, the induced delays between replenishment and sales lead to a desynchronization with the demand and force companies to build up large stocks. Thus, companies must arbitrate to determine a batch size that does not exhaust the gains from economies of scale. If a warehouse orders two trucks at once while it would be possible to spread the orders within the week, this situation does not result in economies of scale but increases stock levels and the associated costs.

While it is not always possible to split batches in production (constraints on reaction times in industrial chemistry…), shipping providesmany levers to do so. First, companies can automate orders to minimize the length between the supply threshold and the replenishment. Second, they can place orders with assortments of different products to reduce the number of replenishments. Third, companies can distribute replenishments evenly to smooth out their stock levels over time.

Predictive modelling

Supply chain management relies on the proper anticipation of future events. Companies determine their adequate production level through a forecast of the demand using predictive models. These models are said to be convex when forecasts absorb and smooth out shocks as reflected by the historical data. By design, these models, the simplest being moving averages, will tend to react slowly to recent variations. On the other hand, non-convex models adopt a different perspective. Instead of being conservative, these models, like linear trends, can propose responses that are not observed in the past. They are not strictly constrained by what has already been observed and can amplify fluctuations at the risk of ending up with overproduction.

The acceptable level of risk generated by predictive models depends on the industry. Non-convex models are optimal for non-perishable products, like luxury watches, where a large part of the production cost is in the materials used. These companies can take advantage of a sudden increase in demand to make a good profit. If the model overreacts, it will still be possible to reuse the materials on another product without incurring excessive losses. On the other hand, convex models are more suitable for perishable products. For strawberries, the product’s value decreases rapidly and an overproduction can turn into a net loss if the prediction model is poorly chosen.

Coordination problems

“Games” occurs when a firm does not react to market conditions but to the anticipated reaction of other players. In “games”, companies stop aligning supply with demand and try to shift the equilibrium in their own interest. For example, when they spot successes, firms can try to corner the market by buying an entire stock. This strategy allows them to ensure exclusivity on a product and therefore to gain market share by attracting new consumers. However, this creates uncertainty and irregular demand peaks for suppliers, leading to coordination problems. In response, suppliers may decide to ration their products to reduce order fluctuations. This is likely to be suboptimal and costly for both supply and demand, as it reduces the quantities traded. The main solution to minimize gaming strategies is to reduce information asymmetries in order to put all players on an equal footing. To do so, some suppliers force their customers to give them direct access to their stock levels. Thus, they avoid misinterpreting customer demand and use this information to secure their stock levels.

Contrarian perspectives

Companies can take advantage of bullwhip effects and do not always wish to mitigate them. For “hit or miss products” (fashion, cultural products, etc.), firms choose to produce more than the level of demand to provide impulses, hoping that a massive diffusion of the product will create a buzz effect. This strategy is used for “winner takes all” products in which uncertainty and variability are intrinsic, and for which the success of a highly profitable product will compensate for the many failures.

At the opposite of bullwhip effects, the supply chain can also be a source of attenuation. For the example of bottled water production, although the demand is mainly concentrated in the summer, the manufacturer produces throughout the year to ensure buffer stocks to cope with the seasonal peak. In this case, consumer demand varies more strongly than production. This mechanism is exacerbated at each echelon of the supply chain and variations in demand are flattened as we move up the chain.

By playing on time and inventory constraints in the supply chain, companies can use the strategy of perceived scarcity to enhance their products’ attractiveness. By deliberately underestimating demand and favoring delays, they create stock-outs, and expectations for their product (queues), thus reinforcing the associated image of scarcity.