00:11 Introduction

01:59 The world of enterprise software

05:07 Epistemic Corruption

08:59 Experimental psychology

14:15 The story so far

15:57 Case Studies, On Vendors (recap)

18:15 Market Research - Direct

18:55 Misguided questions

25:11 Conflict of interest

32:30 Pretense of neutrality

32:59 Wishful thinking

36:40 Market Research - Adversarial

36:55 The silver bullet test

40:12 Qualitative questions

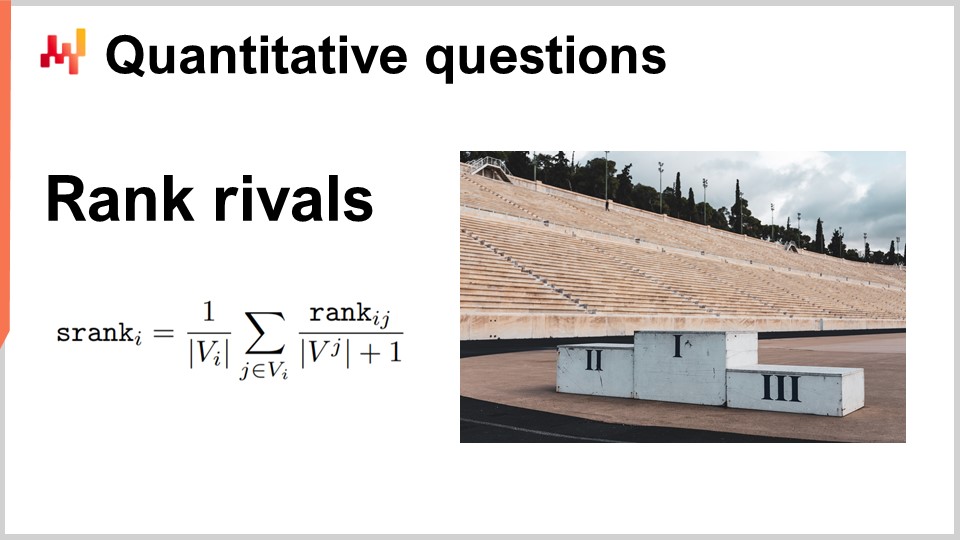

44:01 Rank rivals

46:16 Vendor-on-Vendor format

48:45 Objections

54:47 Recap, market research

59:31 Conclusion

01:01:28 Upcoming lecture and audience questions

Description

Modern supply chains depend on a myriad of software products. Picking the right vendors is a matter of survival. However, as the number of vendors is large, companies need a systematic approach in this undertaking. The traditional market research practice starts with good intent but invariably ends up with bad outcomes, as market research firms end up acting as marketing fronts for the companies they are supposed to analyze. The hope that an unbiased research firm will emerge is misplaced. However, the vendor-on-vendor assessment is a methodology that allows even a biased market research firm to produce unbiased results.

Full transcript

Hi everyone, welcome to this series of supply chain lectures. I’m Joannes Vermorel, and today I will be presenting “Adversarial Market Research.” Modern supply chains are extremely dependent on fairly sophisticated software products, and this has been the case in developed countries for more than two decades. There is a significant concern when it comes to selecting the right tools and vendors, because even the largest companies operating the largest supply chains can’t afford to re-engineer internally every single piece of the applicative landscape, software-wise, that you need to actually run a modern supply chain.

Vendors must be chosen carefully, and the question of interest for this lecture is how to conduct actual market research in the field of enterprise software. My proposition is that there are ways to achieve very reliable results, scientifically even, and there are also ways to conduct market research that are severely misguided, which unfortunately will not give you the sort of results your company might be seeking – to identify the best vendors, meaning those that will generate the highest return on investment for your company. As a disclaimer, I am the CEO of Lokad, which happens to meet the definition of being an enterprise software vendor that operates in the field of supply chain.

The world of enterprise software is vast, to say the least. On the screen, you can see a list of acronyms that reflect typical products found in the landscape of most modern large companies running extensive supply chains. Behind every single acronym lies a concept, and you have typically dozens of vendors operating worldwide, with a couple of them being open-source and the others being proprietary. The company can always obviously decide to re-engineer internally some of those products, but to my knowledge, the proposition that you would like to re-engineer entirely in-house every single aspect of the supply chain is not a very realistic proposition. There is just too much to re-implement, even for very large companies.

In the end, it boils down to actually choosing vendors for those products. Even if your goal is to re-engineer your own in-house solution, it turns out that starting with a proper market research study in the field of interest is probably a very reasonable starting point to know what you actually want to engineer.

Now, the problem I have, and I will start with a piece of anecdotal evidence, is that I believe the publicly available knowledge to sort out all those vendors is of exceedingly low quality. Just to give you an example, if we compare the Wikipedia page on the Suez Canal obstruction incident that happened a few days ago to the Wikipedia page on ERP, it turns out that the page about the Suez Canal obstruction is currently very high quality, well-written, well-sourced, and provides insightful elements. If I look at the Wikipedia page, or any online encyclopedia about ERP, the quality of the page on Wikipedia about ERP is very low, to the point that I would never advise any student to go to the Wikipedia page about ERP to even remotely understand what ERP is about. We have this problem, and it’s even more puzzling because ERPs in their present forms were already kind of stabilized 20 years ago. We have a problem with domain knowledge that not only is of very poor quality, although I’m presenting fairly anecdotal evidence of that, but it’s not even getting better over time.

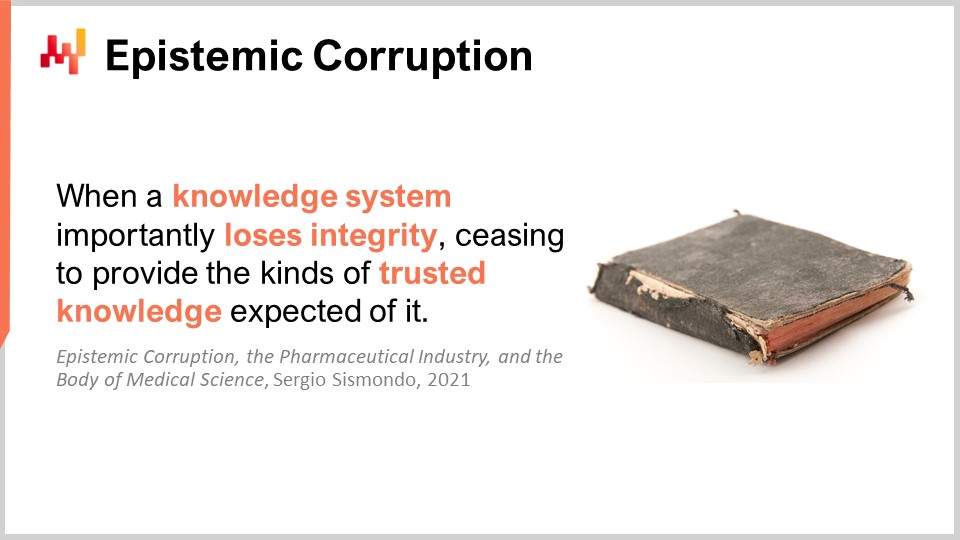

I believe that the problem we are facing here is known as epistemic corruption. Sergio Sismondo defines epistemic corruption as “when a knowledge system importantly loses integrity, ceasing to provide the kinds of trust and knowledge expected of it.” This is an excerpt from a paper published by Sergio Sismondo in 2021 about epistemic corruption, the pharmaceutical industry, and the body of medical science. This problem of epistemic corruption is not specific to enterprise software; I believe that it’s also present in numerous other fields. The reason why I’m paying attention to the field of medical science is that it’s a field that is very mature in this regard, and these problems have been extensively studied over the last few decades.

A fascinating study by the Cochrane Library produced a meta-analysis of over 8,000 medical trials. What they have seen is that when these trials have been triggered with industry funding involved, there is a massive bias in the outcome of the trial that tends to magnify the positive aspects of the treatment being considered. Similarly, there is also a massive bias to underestimate the negative side effects that are associated with the treatment, known as iatrogenic effects. The interesting thing about this large meta-analysis of 8,000 trials is that according to the Cochrane review, there is nothing that differentiates trials funded by the industry from those that are not. All these trials are operated by independent third-party companies, so it’s not like the pharmaceutical industry is doing the trial themselves. It’s highly regulated, highly controlled, and highly audited.

What they point out is that the trials cannot be differentiated in terms of whether there is industry funding or not. The trials are exactly the same, and if you inspect the trials and look at the methodology, everything is indistinguishable. If the funding is not specified, you cannot infer whether it’s a trial that was triggered by the industry or by another party. This is very interesting because it shows that there can be an industry-level distortion that is just caused by the presence of funding.

And again, to quote Søren Kierkegaard, the 19th-century Danish philosopher, “As the world changes, the forms of corruptions become more cunning, but they don’t get any better.” You see, with the phenomenon of epistemic corruption, it’s not like the old school corruption where it’s just a bribe. Instead, it’s more like a distortion of the field of knowledge in its entirety to the benefit of whoever happens to be the dominant vendors at the time.

In order to understand more precisely what is going on, I believe we need to have a closer look at what another science has to say, which is experimental psychology.

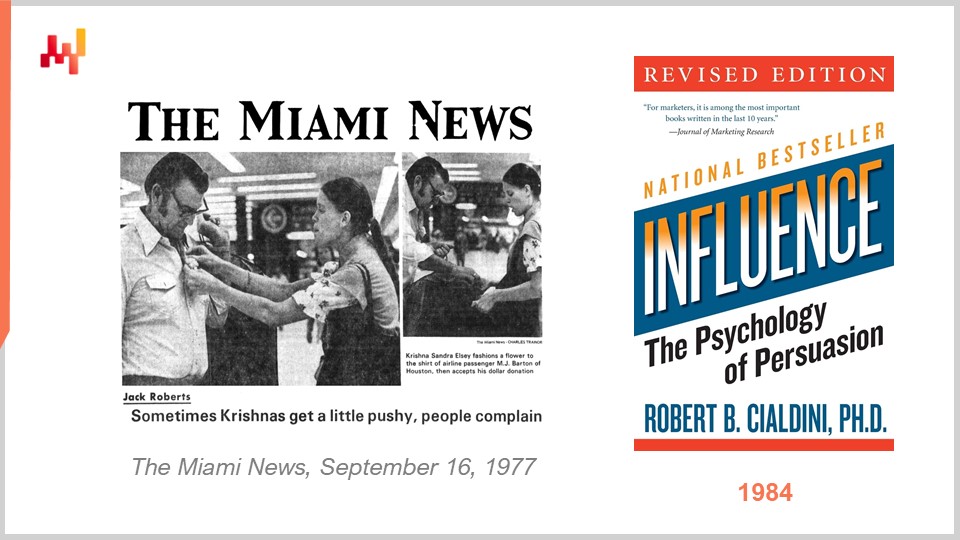

Robert Cialdini, a researcher, published a fascinating book called “Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion” in 1984. Cialdini is a very popular character. As a researcher, he decided to go three years undercover to infiltrate the most influential organizations of his time, which included telesales companies, lobby groups, and religious movements. His idea was to observe what sort of influence techniques were at play. He spent his career first collecting information during those three years underground and then later, as a researcher with his peers, replicating the insights gained during his undercover years in more controlled environments to produce rigorous science on top of those initial insights.

The infiltration method was more mundane than it seems. Mostly, it was about applying for a job, getting hired, undergoing the training, and sticking around for a certain period of time to get a feeling of how things were operating. Cialdini identified among the influence mechanisms a very simple mechanism called reciprocity. Reciprocity is something very intuitive: if I do something good for you, you will be inclined to do something good for me. This is something most humans react to.

However, the surprise for Robert Cialdini was not that reciprocity exists, but that it can be abused in ways that are absolutely spectacular. If you play your cards right, you can get a completely outsized effect out of this reciprocity mechanism. To illustrate this, Cialdini gives the example of the Hare Krishnas, a religious movement that emerged in the late 1960s and grew during the 1970s. The Krishnas became one of the most successful flower vendors of all time by pioneering a sales technique that had staggering results.

The technique was very simple. They were selling flowers in airports and would pick passengers at random, giving them a flower. When the passenger tried to return the flower, the Krishna would say, “No, no, this flower is given, but you can decide to pay for it if you wish to.” So the Krishnas were simply giving away the flowers and telling people that they could pay whatever they wanted, even nothing if they preferred.

The surprising thing was that not only did they manage to sell an order of magnitude more flowers with this technique than any other flower vendor ever managed to do in an airport, but the amount of money the Krishnas were getting per flower was also an order of magnitude higher than what any regular flower vendor would get in an airport by just selling a single flower. This technique was so successful that it massively contributed to funding the Krishna movement during the seventies. Cialdini later reproduced this in controlled environments, mostly with students, and found it to be a very interesting mechanism that smartly abused the concept of reciprocity. It forced people to state in monetary terms how much they valued what had just been given to them. People wanted to clear their debt because they had been given something and didn’t necessarily want to owe a stranger. This ended up being a very effective sales technique.

In fact, the technique was so effective that giving away flowers eventually got banned in most U.S. airports in the following years. I believe reciprocity, and more specifically the abuse of reciprocity, is really at the crux of the issues currently plaguing enterprise software, and we will be getting back to that. This psychological mechanism is at play.

This lecture is the fifth lecture of my second chapter. In this series on supply chain, in the first chapter, I presented my views on supply chain both as a field of study and as a practice. In particular, I pointed out that supply chain is essentially a collection of wicked problems, as opposed to tame problems. It’s problems that don’t lend themselves easily to straightforward analysis, just because we have so many wicked aspects where what other people do in the market can completely undermine the validity of the answer to a given problem.

I decided to devote the entire second chapter to methodology, on ways to cope with and obtain rigorous results when facing all these wicked problems. We have seen a series of methods, some qualitative and some quantitative. Supply chain personae was a qualitative method, while experimental optimization is more on the quantitative side. Today, we are back to the qualitative problems of conducting market research in the field of enterprise software, with a hint of specific interest in supply chain problems. Although what I’m presenting today is not exclusive to supply chain software, it applies more generally to all pieces of enterprise software.

Let’s recap what we’ve seen in the first lecture of this second chapter, the personae lecture. We have seen that vendors do what vendors do. When you ask a question to a vendor, they are just going to present what they are trying to sell in the most favorable light possible. Expecting anything else is kind of foolish, and this notion has even been embedded for centuries in Roman law with the idea of “dolus bonus,” the good lie. Yes, merchants lie, but it is kind of expected. This is what happens when you have something to sell, and it’s not even fraud – it’s legally admitted.

I believe more specifically that another problem arises from case studies, as we’ve seen in one of my previous lectures. Case studies, which are invariably positive, are essentially pieces of work that demonstrate the return on investment that can be obtained by deploying a solution of some kind. Case studies that demonstrate negative returns are exceedingly rare. What I’ve shown is that by bringing a client or an analyst into the picture, you don’t get a research format that is more objective; on the contrary, you get something with even more bias. Essentially, you pile up the bias of the vendors themselves with the bias of the client company, which has plenty of interests of its own. If there is a market research firm involved on top, then you also get those biases piling up.

In conclusion, as I stated in a previous lecture, if you look at case studies in the field of enterprise software, it’s essentially glorified infomercials. This is “dolus bonus” at play – it cannot be trusted and cannot be used as a foundation if we want to have some kind of trust and knowledge that will let us assess the respective qualities of the vendors.

Now, let’s dig into how we can actually conduct market research. I will first present how not to do market research because there are plenty of intuitive but unfortunately incorrect approaches. I call this the “direct market research approach.” Then, we have the “adversarial market research,” which I believe is a vastly superior form of market research that has many advantages, the first one being that you can actually get results you can trust, which is a massive plus.

Classical direct market research typically follows a simple and intuitive recipe. It can be conducted by a company that operates a supply chain and wants to find a vendor to solve a specific problem, consultants who assist companies in making strategic choices, or specialized market research firms. The typical methodology followed by all these actors when it comes to market research is just to ask questions.

First, you compile a list of questions, such as, “Can you do time series forecasting? Do you support minimum order quantities? Do you have a case study on aerospace supply chains?” Then, you compile a list of vendors and send all those questions to every single vendor. You get the answers, consolidate them, and then through analysis of the answers, you gain insights into the market and can sort out who is delivering the most promising value for the company.

I believe that this approach is deeply misguided on two accounts that completely undermine this direct method. The first one is that this method extensively relies on the fact that you will get honest answers from the vendors. However, you are facing a situation where, with “dolus bonus,” every single answer that you will get from the vendor will be a lie to some extent. I’m saying this as a vendor myself; this is just what vendors do. When you have a product, you say that it’s going to be better than any other product. This is just the nature of vendors. If you ask an enterprise software vendor if they can do something, the answer will always be “yes, we can,” no matter what the question is. Usually, the problem is that these questions are subject to interpretation. For example, if you ask if a vendor supports MOQs, it depends on exactly what you mean by supporting MOQs. If it’s just about having one field where you can enter an MOQ and have a completely trivial numerical recipe attached to it, then yes, any enterprise vendor is going to say they support MOQs, but that’s not helpful. Case studies and references are even worse because they have more bias than the blunt specification of the enterprise software products.

On the second front, there is another problem just as big as the first one but of a completely different kind: you don’t know which questions to ask. If you look at the history of science, you’ll see that most of the historical scientific breakthroughs were not about getting the answers. The breakthroughs were usually about figuring out the right questions to ask. Knowing the right question is usually vastly more demanding and difficult than actually getting the answers. For most questions, getting the answer is just a pedestrian effort. Once you know the question, then yes, it will take time and resources to get an answer, but this is a very straightforward process. However, what is very difficult is that you don’t even know which questions to ask. This is where I say this methodology is misguided because you compile a long list of questions that usually completely miss the point. The entity, which can be a client company, consultants, or market research firms, doesn’t know what the key challenges are. They don’t have the sort of insider knowledge that vendors do because they are on the front line and typically have been playing this game for decades.

By the way, as a casual observation, I typically notice that when consultants are involved, the problems are usually amplified because consultants, in order to justify their fees and the mission, inflate the number of questions. Again, it’s not because you have a bigger pile of lies that you’re going to get any better results. It’s just going to add to the confusion, and you’re not going to make any headway toward the truth.

At the crux of the problems here, we see that we have a conflict of interest. This is the problem that is impacting vendors, which is why vendors can’t give you completely truthful answers about the respective qualities and weaknesses of their solutions because it’s not what vendors do. But I believe that there is a much more insidious problem about conflict of interest from the market research firms, which are the elephant in the room. They have massive problems of conflict of interest of their own, and let’s have a closer look at that.

First, just to recap, the two golden rules of conflict of interest are: 1) Conflict of interest must be publicly stated. By the way, this is what I did in the very first lectures of this series. I presented the fact that I am the CEO of a company that is an enterprise software vendor, and I reiterated this disclaimer in this specific lecture due to the topic of interest. 2) The second golden rule of conflict of interest is that you don’t get to decide if you have a conflict of interest. It’s not up to you. That’s a mistaken assumption. You have a conflict of interest if, according to general principles agreed upon collectively, your situation presents a conflict of interest. It’s not an assessment that you can make on yourself. There are general principles that apply to you and define whether you have a conflict of interest or not.

Now, if we want to examine the specifics of conflict of interest, the World Bank has a very insightful guide intended for procurement teams on conflict of interest. They present all the classical forms of conflict of interest, such as bribes or having well-placed relatives, so you can have direct monetary gains. I will be putting the link to this document in the description of the video later. However, these old-school conflict of interest situations are not what I believe to be of interest in the world of enterprise software. Quoting Søren Kierkegaard, “As the world changes, the forms of corruption become more cunning, but they don’t get any better.” In the software industry, we have developed more cunning forms of corruption.

So, what are the specific problems? First, I would say trade shows. Trade shows on their own are just fine, but the problem arises when the trade show is organized by a market research firm. In this situation, the market research firm ends up taking the vendors as clients who will suddenly become exposed in the trade show. If you have a trade show organized by a market research firm that invites vendors to be featured in the trade show for a price, which obviously goes to the market research firm, you have an absolutely massive conflict of interest. By the way, if we were to do that in regulated domains like medical science, for example, in the pharmaceutical industry, doing that would be a straight “go to jail” card, like in Monopoly. So, this is pretty much textbook massive conflict of interest. There are also more elaborate ways, such as restaurant invitations or travel invitations, where an analyst of a market research firm is invited by a vendor to a restaurant or an event. This qualifies as a conflict of interest. Remember, as I pointed out with the work of Robert Cialdini and his peers, the reciprocity principle comes into effect. If you play your cards right, you can expect outsized returns. So, yes, it’s just an invitation to a restaurant, but you can get a very large effect from that. It’s just like the Krishnas who manage to sell tons of flowers with a simple gesture of goodwill.

Another elaborate mechanism consists of job lending. If you happen to be an analyst in a market research firm with some notoriety, ten years down the road, you might be expecting to be hired by one of those vendors. I don’t mean six months down the road, but ten years. People can afford to have the long view, as this is an established industry, and players have been around for a very long time. You cannot just look at the conflict of interest as if it were something with an instant monetary gain. Enterprise software is a sophisticated industry. People can look far into the distant future, and they can have a conflict of interest because they anticipate that even ten years from now, they will earn a position in a vendor due to the fact that they have praised this vendor in the past.

As far as market research firms are concerned, you can also amplify your conflict of interest, for example, by offering coaching and consulting services directly to the vendors. This creates an even bigger conflict of interest because you extend your reach into all sorts of missions. Finally, to point out the modern way to look at conflict of interest, you really need to look at the corporate structure. It’s not about whether a particular person earns money directly. If the employer is earning money and has a conflict of interest, then all the employees of the given company have a conflict of interest. Even from modern standards, we can’t say that conflict of interest stops at the corporate boundaries. For example, if you have two companies with the same shareholders, a conflict of interest for Company A can permeate Company B just because they have shared ownership between the two companies. That’s the sort of problem we’re facing.

In conclusion, when I look at market research, especially from specialists, I see that there is a pretense of neutrality, but the reality is not. The conflicts of interest are so prominent that you don’t get neutrality; what you get is pay-to-win. Again, that cannot be escaped.

When I look at market research in the field of enterprise software, I see that there is a lot of wishful thinking floating around. Wishful thinking where people say, “Well yes, we have all those conflicts of interest, but it’s okay, we have a code of conduct.” However, it doesn’t work like that. That’s the sort of thing that was illustrated, for example, by the Cochrane review of those 8,000 trials I mentioned today. Even when you have everything in place, including independent organizations, interest can permeate. So, it’s not because you have a code of conduct. In the field of medical science, which has heavily regulated operations and is heavily audited and controlled, they still have extensive bias, as demonstrated by the Cochrane review. How can it be any other way in the field of enterprise software, where there is absolutely not the same degree of care and attention paid to those elements? Code of conduct changes absolutely nothing.

The idea of having silos or business units also doesn’t address the problem. It’s not because a market research firm has two distinct business units, one to deal with trade shows and another containing analysts, that it addresses any problem at all. The conflict of interest will permeate the company across the board. It’s just an illusion that, just because in a company you decided to have a left branch and a right branch, the branching of the organogram itself is going to stop the conflict of interest from propagating. Only a very naive person would believe that.

Another aspect of wishful thinking is that people think, “Oh no, it’s okay, we are honest.” This is not the problem. I believe, and that’s also the conclusion reached by the Cochrane review, that conflict of interest is not about honesty or dishonesty, it’s about bias, most of it being unconscious. You never think about being biased yourself; you just think what you think. You can exhibit tons of bias even if you don’t think so. This goes back to the experiment carried out by Robert Cialdini in his field, where you can engineer bias, and when people are asked to do self-assessment, they remain very confident in their capacity to remain unbiased. It has nothing to do with honesty, and you can obtain severe bias with perfectly honest people.

The idea that you can address the problem through non-profits is also unrealistic. Nobody is going to do market research on super boring topics like, let’s say, EDI (Enterprise Data Interchange). You have a lot of enterprise software products that are exceedingly boring to engineer and review. Nobody could be expected to do that for free, just like you can’t expect people to audit accounts of companies for free. So, the idea that you can have some sort of non-profit organization step up is just not realistic.

So, how can we actually conduct market research? I believe that the simple idea, if you want to conduct proper market research, is to have an adversarial line of thinking.

By the way, I borrowed this idea from Warren Buffett, one of the richest men on Earth. He is probably among the most successful investors of all time. He has engineered a very simple recipe. Although this recipe is very public and has been shared by Berkshire Hathaway, the company Buffett founded over six decades ago, it has never really been copied despite making perfect sense. Buffett has said in numerous interviews and memos that his primary technique for market research is the “silver bullet test.” He asks, “If you had a silver bullet and you could shoot it to get rid of one of your competitors, who would it be?” This is a question that Buffett asks the companies he surveys.

As an investor, his job is to conduct market research and identify which company in an industry he should be investing in. The problem faced by Warren Buffett is that whenever he tries to survey the market, every single CEO who is doing a decent job will present a distorted view of their own company in a highly favorable light. Talented CEOs are typically very good at seducing investors. If Buffett asks direct questions, even financial ones, he ends up with a big pile of lies. Anyone familiar with corporate finance knows there are thousands of ways to present numbers, all completely legal, to make a company look like it’s thriving despite hidden problems.

Berkshire Hathaway uses this simple question to identify the actual good players. They don’t ask questions about the company itself; they ask the company about its peers. This approach negates almost entirely the problems of conflict of interest.

The way I propose to conduct market research is exceedingly simple. It’s just two questions, addressed to software vendors: “Present yourself” and “Present your peers.” No other questions whatsoever. You could eliminate the first question, but out of courtesy, it’s better to ask people to present themselves first, so it doesn’t feel too rude. Fundamentally, it’s the second question that is truly of interest.

If we go back to the two problems I pointed out for the direct market research approach – first, the massive distortions, and second, not knowing which questions are the correct ones to ask – it turns out that if you use this approach, you can address these issues. Concerning distortion, if a vendor tells you that another vendor, a competitor, is actually a very talented rival, you can trust that. It is not in the vendor’s interest to admit that another vendor is a threat to them or that they have some admirable pieces of technology. If they admit that, you can trust that it’s actually true, or at least have greater confidence in it. The vendor itself might not know the market perfectly and can make mistakes, but they have more insider knowledge.

When it comes to presenting peers, vendors can also present the relevant questions that you should be asking but might not think about. For example, if you ask about sales forecasting, a vendor might suggest you should be asking about demand forecasting instead, as you’re interested in future demand, not future sales. Another vendor might suggest focusing on probabilistic forecasting or lead time forecasting, while a fourth might argue that focusing on forecasting could make your supply chain fragile against unforeseen events and suggest thinking about buffers instead. The only way to discover these perspectives is to let vendors present their peers and the strengths of their competitors. So, you only need to ask two questions: “Present yourself” out of politeness, and “Present your rivals,” which is what really matters.

Once you have a presentation of rivals, you can ask the vendor to rank the vendors they have just described, starting with their best rival and going down the list to the rivals they are most indifferent to. This is it.

There is a misguided idea that you can ask vendors to rank their peers against 20 different metrics, but that is not realistic. As a vendor myself, my perception is not that ingrained about the competitive landscape. However, when it comes to assessing the best rivals to the most indifferent ones, this is a safe bet. To conduct such a survey, the process is straightforward: identify your vendors, send them the two questions, collect their qualitative answers in plain text, and gather their implicit rankings. You can even build a synthetic ranking with a simple formula, which I provide an example of here. The specifics will be given in a link attached to this talk. With this simple, unbiased ranking mechanism, you can sort out the field of vendors that you believe to be relevant to your company and identify emerging leaders.

What I’ve just presented is fundamentally what I refer to as the “vendor on vendor” format. It’s inspired by the silver bullet perspective pioneered by Warren Buffett, consisting of two questions, the second of which implicitly contains a ranking. When it comes to consolidating answers, there’s no edit needed, just minimal curation to eliminate low-quality or irrelevant responses. The exercise is simple: just collect the information.

What you get in the end is something that doesn’t eliminate conflicts of interest but neutralizes them through conflicting views. The beauty of this vendor on vendor assessment is that, due to the conflicting views, you know that every single answer is biased. However, in aggregate, all of that can give you a very impartial view of the market and reveal the truly good companies operating within it. This methodology is the essence of the success of Berkshire Hathaway. Interestingly, I’ve been approached by many venture capitalists, but I’ve never seen any investor using this technique. It’s intriguing to me that the most successful investor of all time uses a method that is simple and sensible, yet often overlooked due to its deceptive simplicity.

When I started to probe people new to this domain about this idea, a lot of objections were raised, and they are very interesting. I will address these objections. The first objection is related to market research firms. They argue that there is nothing to see here and that their key insights are necessary for an unbiased market view. I strongly disagree with this statement, especially for those firms that organize trade shows or events where vendors are invited. I believe that it’s just a pretense.

When considering the secret objections that they cannot tell me, it’s clear that there is a lot of money on the table, and the vendor on vendor study has one massive problem for market research firms: it’s very cheap to conduct. This is exactly what Warren Buffett was saying about his own techniques in an interview. The silver bullet test can be conducted in a matter of hours, allowing for the identification of key players in any industry. It’s dramatically efficient and removes all the noise.

When conducting a market research study, your goal is not to become an expert in the specifics of a solution yourself; rather, it’s to identify the good vendors in the market. Some vendors were enthusiastic about the vendor on vendor assessment, while others, fellow competitors of Lokad, were more negative, believing it to be a bad idea. My counter-argument is that the assessment will only be as negative as you make it. If you say good things about your peers, the study will be fairly positive.

Another class of objection is from vendors who claim not to know their peers. My response to that is: how can you claim to have state-of-the-art technology if you don’t know your peers? To claim superiority in any aspect, you must know what the other companies are doing. Otherwise, what’s your baseline for comparison?

I believe that the secret objection is the imposter effect. To clarify, I’m not talking about imposter syndrome, where someone feels like an imposter despite having expertise. The imposter effect refers to actually being an imposter, with little or no expertise. The problem with this sort of study is that it threatens vendors who pretend to have superior offerings but have nothing to support their claims. They fear being exposed as impostors.

Now, let’s discuss the client’s objections. Some clients believe that the study doesn’t answer their specific questions. This perspective relates to the direct market research approach, where clients want to ask various questions like, “Do you support this?” or “Do you support that?” Once people understand what these questions are about, they realize that these questions are not very interesting and just a facade. Superficially, clients can object that it’s not exactly their questions being answered, but this is mostly a bad faith argumentation.

I believe that the secret objection is that asking these questions and presenting peers feels weird, even borderline rude. This is one of the simple explanations for why this method, which made Berkshire Hathaway successful, is not widely adopted. People are afraid of doing weird things, even more so than doing bad things. These questions make people feel weird, but they are simple and have excellent operating efficiency.

To recap on market research, you have the direct method that relies on self-assessment. Vendors give their opinions about themselves, and the methodology relies on expecting honest answers. However, this method is undermined by conflicts of interest, either from vendors or market research firms.

Direct market research is characterized by large overheads, as you end up asking many questions, which results in more answers and a massive study. This leads to the need for consultants and extensive time investments. In terms of the endgame, it converges towards a pay-to-win model due to the conflicts of interest faced by market actors.

The adversarial perspective, on the other hand, relies on the assessment of others – peers and competitors. You can still expect bias, but it will be in the interest of the client company trying to make an assessment. This approach of adversarial market research starts from the understanding that bias exists, and it aims to take advantage of that instead of trying to mitigate it. As a result, you don’t end up with a conflict of interest, but rather a study that represents conflicting interests. The consolidation of these conflicting interests can give you a very impartial view of a market.

In terms of positive qualities, the overhead for adversarial market research is minimal. It requires significantly less effort to conduct compared to a direct market research study. Additionally, because the resulting material is relatively limited, you don’t have to delegate your judgment to a third-party company. You can keep the decision-making process in-house. For companies operating supply chains, it’s crucial not to delegate judgment to a third party, as your interests are best served by your own judgment. If you delegate your judgment, this third party will likely take advantage of you over time.

Interestingly, in terms of the endgame for adversarial market research, which doesn’t meaningfully exist yet except as practiced by Berkshire Hathaway, we can expect a return to the original business model of most market research firms, where people paid to access reports and judge their content. With this method, we can even envision a world where market research firms operating along these lines can sell very cheap reports, as it’s inexpensive to conduct an adversarial market research study.

In conclusion, I believe that epistemic corruption in the field of enterprise software is severe, and the consequences should not be underestimated. When domain knowledge is debased, massive problems arise. For supply chains, it means they will remain more wasteful than necessary, not achieving as much progress as desired and not generating the expected profits. These problems are widespread, and considering that the world runs on these large supply chains, which are at the core of our modern industrial civilization, this is a very severe issue.

While nobody is dying as a result, a lot of money is being wasted – money that could be invested or reinvested in better solutions. I believe that adversarial market research is a simple piece of the puzzle to address the issue of epistemic corruption in the field of enterprise software vendors. I would like to present my special thanks to Stefan de Kok and Shaun Snapp, who contacted me a few weeks ago and gave me some hints and the original idea of having a vendor assess another vendor. The views I’ve presented today are mine and mine alone; the initial idea of having a vendor assessing another vendor was presented by Stefan de Kok and Shaun Snapp.

By the way, I did conduct my very first vendor-on-vendor study, and I published this study on www.lokad.com.

Currently, it’s a minimalistic study that presents 14 vendors that I consider to be rivals or peers. They’re ranked from the company I admire the most to the one I feel is least relevant. I would like to extend an invitation to all my competitors to join this study by inserting their own views. It’s relatively cheap, can be done in a few hours, and it’s not even one-tenth of the effort it takes to answer a request for proposal or request for quotation. As enterprise vendors, we provide these sorts of answers all day long as part of our regular activities.

I truly believe that we have a unique opportunity to establish a superior form of knowledge and disrupt the market so that we can exit the deadlock currently plaguing the world of enterprise software. Now, I’ll be having a look at the questions.

Question: Krishnas worked for free. High-discipline fields will never work for free. The comparison is weak.

Yes and no. When you say Krishnas worked for free, that doesn’t explain how they were absolutely stunning vendors. They achieved a degree of proficiency in selling flowers in airports that was unrivaled. The question is whether you can sell more, and on the baseline of being able to sell tons of flowers, Krishnas had stunning results to the point that the practice was banned because it was so effective as a sales technique.

The comparison is not weak. They had an incredibly efficient sales technique, which Robert Cialdini has studied extensively. They reproduced these results under controlled environments, and it’s not specific to flowers. You can achieve the same results under many conditions if you know how to abuse the principle of reciprocity. This mechanism has been extensively studied in experimental psychology, and it is now severely frowned upon when vendors play these games. Regulations have been put in place worldwide to put an end to these sorts of shenanigans. So, I believe the comparison is relevant. The key is, is there a mechanism to abuse this principle of reciprocity? It could have been any other religion, but the anecdote just happened to involve this religious movement.

Question: When a decision-maker doesn’t know which questions to ask and instead asks the vendor about the demo, which the vendor accepts to do, does it qualify as abused reciprocity from your standpoint?

No, this is not reciprocity because you expect the vendor to do a demo. When a client company interacts with a vendor to get a demo, it’s not because they spent half an hour of their time giving the demo that the client will feel they owe the vendor something. I don’t think it works that way, as people know it’s just a demo. However, the real problem is that what you get from a demo is a very distorted view.

For example, during a demo, don’t expect a vendor, including Lokad, to present any weak aspects of their solution. All enterprise vendors I’m aware of make sure their demos don’t hit any bugs. Even if you try to be very honest as a vendor, don’t expect me to do a demo in which I demonstrate the bugs of my products. That’s not what I’m going to do. So, when you do a demo, it’s perfectly fine, but you’ll essentially get a distorted view. Don’t expect the demo to be the truth; it’s going to be like a showroom car that looks way more beautiful than it is in reality.

Question: On the point of presenting your rivals, you are assuming that vendors have unbiased and unlimited knowledge about the competition. How many demos of vendors have you actually seen? Analysts and consulting companies have seen all the tools.

I’ve been the CEO of Lokad for 12 years, and I’ve seen dozens of competitor demos. I’ve spent entire weeks reverse-engineering all the publicly available materials. When I try to improve my own product, I first try to copy whatever I can from my competitors. As the CEO of Lokad, I’ve spent an enormous amount of time on this, and I believe I have tons of insider knowledge.

The problem with consultants is that, while they may have seen the demos, they haven’t tried to re-engineer the same things themselves. When a competitor says they’re using a specific machine learning technique that works great, what do you do? You just grab the open-source machine learning toolkit of the day and try it for yourself. As a vendor, you can see all sorts of problems that might arise with these techniques. Maybe one of your competitors is using a specific technique, but when you try to replicate it, you see that, while there may be some good points, there might also be tons of hidden flaws. You only see the problems if you actually try to re-engineer the solution yourself and put it into production.

The problem with consultants is that they see the demos but haven’t tried to re-engineer the solutions themselves. Re-engineering is crucial because one of the hidden flaws in enterprise software is maintainability. It’s not just about producing a piece of software and making it work on day one; it’s about ensuring that it’s still maintainable ten years from now. This is something you only see as a vendor because if you produce something that is unmaintainable, it will complicate all the downstream software development you want to do.

Warren Buffett points out that market players always see the bad stuff, but they only speak publicly about the good stuff. When it comes to assessing vendors, Alex asks how to avoid or detect the effect of favorable assessments given without any reason but to look better than they actually are. The thing is, my competitors are not my friends. Most of my competitors are companies that are hundreds of kilometers away from Lokad. I don’t have to be friends with them; I don’t live with them.

The problem with 360-degree assessments inside a company is that it can become toxic quickly because you’re part of the same team. If you’re too honest and say something bad about someone, you have to live with the consequences while working in the same office every day. It’s challenging not to befriend people you work with all day long. When it comes to the assessment of companies by other companies, vendors will have much less sentimentality about saying something bad about a competitor. They certainly won’t praise a competitor they know isn’t a good player just to avoid displeasing them. You see, there’s a sort of effect where you don’t want to displease your competitors. I don’t have to please my competitors, and I certainly won’t praise competitors that don’t force my admiration.

I believe this methodology is more applicable to commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) software. Many clients face “make or buy” choices in their digital and data supply chain transformation. The difficulty lies in defining the scope of the research: packaged software, platform, or full custom. I believe these techniques apply to numerous fields, and if you look at the experience of Berkshire Hathaway investing in dozens of industries, it kind of applies to anything.

My specific personal interest lies in enterprise software, which has always been a mix for decades. There’s always an extensive degree of customization involved, and this is true for the largest vendors as well as the smallest. This is especially relevant when it comes to supply chains, which tend to be complex and unique. No two supply chains are built the same way.

I believe this methodology can be applied to vendors, whether they have off-the-shelf products or more customized solutions. In the realm of enterprise software, which is the topic of interest, there is no relevant disconnection in the sort of build or buy decision. The challenge lies in not knowing the right questions to ask. When you engage with your peers, they will give you hints on the technologies that are worthy of admiration and the good directions to take, even if you decide to do it in-house.

The problem with enterprise software is that there are so many options. For every problem, there are countless directions to go. The roads are endless. Leveraging this sort of market research allows you to gain insights from those who have done it before, offering quick and cheap feedback on what works. If you say you already know more, you position yourself as being capable of forming a superior technological assessment than the vendors themselves. This might be the case, but it’s a bold statement to make.

A large company can make this sort of move for a couple of products, but it’s not realistic to say that you’re going to engineer in-house every single product in a superior fashion. There are very few companies that could, for example, re-engineer the Linux kernel in a way that is superior to the original. There are just a few software engineers on Earth with the skills it takes to deliver a better product. Even if, in the end, you want to do something in-house, it’s so cheap to do adversarial market research. You can do it in a day. Just send two questions to 20 vendors, and you’re done. The sort of answers you will get are fairly short, so it’s not going to take weeks of your time to form a very firm idea on who the key players are and what good ideas they are pushing forward. Again, you don’t even know what the good ideas are that you should be looking at.

Question: Solution versus solution assessment is much less important than the quality of implementation. By and large, all systems do the same thing. It’s about how it’s implemented, how it embraces the company. Very rarely do we choose the wrong system. It’s more that we couldn’t implement it properly or our users did not cope with the challenge.

I very much disagree with the idea that all solutions do the same thing. While I have an opinionated perspective, if you look at the technical specifications of Lokad, you’ll see that it’s a very different beast compared to the vast majority of enterprise software vendors. As the CEO of a software company, I believe my company is better, but that’s an obvious bias. However, I believe that without too much bias, we are exceedingly different. I’ve also talked to people I consider as competitors, and they believe they are different too.

I challenge the fact that all vendors are the same. I’ve reviewed dozens of vendors, and the core technological design decisions can have an absolutely dramatic impact on everything that follows. Vendors can vary in ways that are incredible. It’s mind-boggling how different approaches can be taken to the same problem. So, I really challenge this assumption.

In terms of implementation, I agree that it matters. But when you pick a vendor, it’s part of the assessment of your peers. For example, in the assessment of the peers I’ve made about Lokad, I present certain other vendors and say they have a very good ecosystem to do the support and the implementation. When you admire a peer, you can admire the sort of ecosystem they have surrounding themselves with, and that can have a lot of value. Those ecosystems of people that can do the implementation on top of your product don’t just fall from the sky; it takes a lot of effort from the vendors themselves.

So, as part of the vendor assessment, the question is often about presenting your peers and what you admire the most about them. There is no limit. You can say anything you want, and you can say that you admire one of your peers because the ecosystem they have created is just fantastic, and they have a superior capacity to execute. This can be completely orthogonal compared to the technology. Again, that’s not the point I’m making. The questions are very open-ended, and vendors can say anything they want about their peers. There are no boxes to be ticked.

I guess that’s it for today. Two weeks from now, it will be the same day of the week, Wednesday, and the same hour of the day, 3 p.m. Paris time. I will be presenting “Writing for Supply Chain.” See you next time.